In the dark years of the regime illustrators managed to make their art flourish in film posters. After 1989, the Czechoslovakian art of posters could not survive the advent of the Hollywood model

Infinitely creative, sometimes sharp, biting, and often surreal. These are the adjectives most frequently attributed to the film posters produced in Czechoslovakia during the communist period. At times bizarre, yet always ingenious. It may be possible that the names of Zdeněk Ziegler, Karel Teissig, Bedřich Dlouhý and Jiří Balcar don’t mean anything to you. Yet it is likely, given that these are some of the most important Czechoslovakian graphic artists ever, that you have already seen some of their works. The posters, besides being a reflection of Czechoslovakian art in general, are a useful tool to better understand the history of the country, especially the works that promoted foreign films nowadays indicate which “external” influences were allowed or not. Slowly, the graphic material produced in the era is now coming to light, with more and more shops and websites which sell the best works, testimonies of other times. However what is behind the peculiarity of these posters? Why this surreal style, with posters that sometimes have little or nothing to do with the films they refer to?

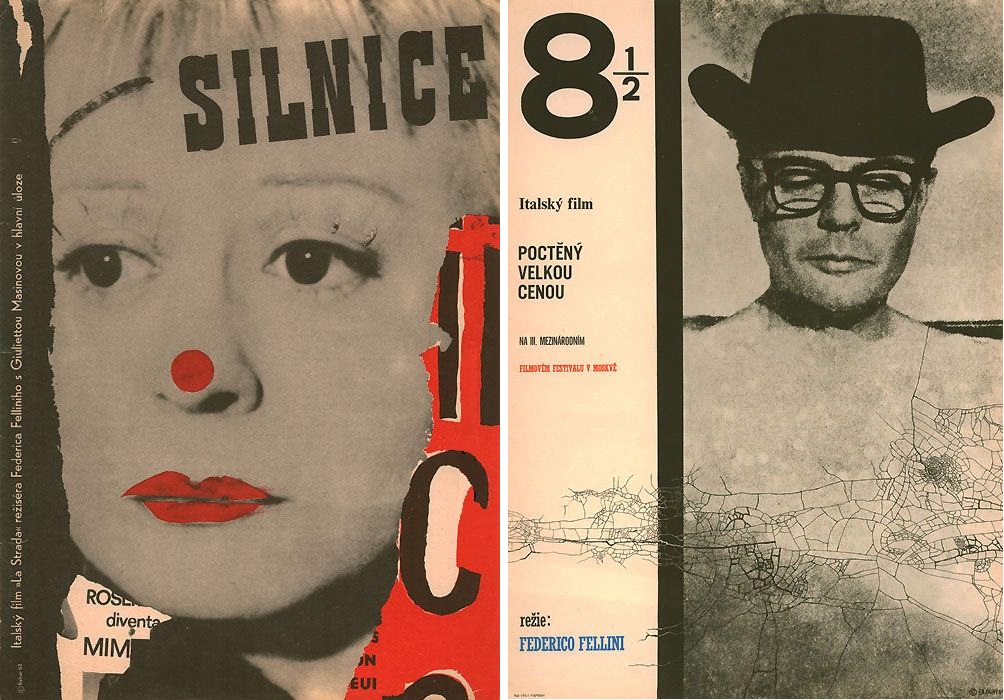

Unsurprisingly, the main reason is of an economic nature. In Czechoslovakia, as in Poland (the only other country that produced posters comparable in terms of boldness and surrealism), the cost of importing posters from abroad was high, and therefore the best painters, illustrators and artists were hired to create their own posters using only their imagination, without the marketing dictates that existed in other countries. Curiously, thanks to this freedom of expression and unbridled creativity, the authors of the poster art, unlike in other art forms, could experiment, without being monitored and viewed with suspicion by the authorities. Moreover, the fact that artists often worked without seeing the films for which they designed the posters, basing their work often only on the press clippings and the title, explains the unique and very personal interpretations of films on the posters, which were at times even misleading.

Unsurprisingly, the main reason is of an economic nature. In Czechoslovakia, as in Poland (the only other country that produced posters comparable in terms of boldness and surrealism), the cost of importing posters from abroad was high, and therefore the best painters, illustrators and artists were hired to create their own posters using only their imagination, without the marketing dictates that existed in other countries. Curiously, thanks to this freedom of expression and unbridled creativity, the authors of the poster art, unlike in other art forms, could experiment, without being monitored and viewed with suspicion by the authorities. Moreover, the fact that artists often worked without seeing the films for which they designed the posters, basing their work often only on the press clippings and the title, explains the unique and very personal interpretations of films on the posters, which were at times even misleading.

Despite a tradition of film posters that had already existed for decades, it was their Polish neighbours who gave the necessary push to the Czechs to “raise the bar”. An exhibition of Polish posters at Dům uměleckého průmyslu (the “House of applied arts” of Prague), in June 1954, opened the eyes of the representatives of the cinemas in the country. The works on display, created by masters such as Henryk Tomaszewski and Jan Lenica, were considered the embodiment of the pride and national character of Poles, with a unique graphic style that was totally independent from the Soviet archetypes. It is said that Projekt, the Polish magazine of visual arts, was the source of inspiration for the next generation of Czechoslovak artists. The influence was visible, but the styles of the two countries were different. The Poles showed an increasingly painterly approach, while the Czechs also experimented with other techniques, such as collage and wood engravings, but often with surrealistic tendencies not dissimilar to the former.

The explosion of the Czechoslovakian industry was inevitable, and a group of new artists like Karel Teissig, Bedřich Dlouhý, and Jaroslav Fišer, came into the spotlight. Once they grasped the potential of the art form, film studios did not want to risk ending up with a below par poster in their hands. The artists were chosen very carefully according to their characteristics and skills, often by the propaganda department of the office of film distribution. The illustrator Stanislav Duda (born in 1921), displayed a talent for comedy, Karel Teissig (1925-2000) had a way of expressing himself which was very suitable for suspense and mystery movies, as well as the horror genre. Teissig, heavily influenced by jazz, with a deep knowledge of the literature and the art world of Paris, was the first Czech artist to create a poster that proved to be successful abroad: it was his masterpiece for the French film The Possessors (Les Grandes Familles) with Jean Gabin, also winner of the prestigious Toulouse-Lautrec award in Paris in 1964. His vision of a movie poster as the philosophical reflection of the artist influenced the next generation of graphic artists immeasurably, as did his motto “a successful film poster should be beautiful, somewhat mysterious, highly intelligent, brief and inventive”. Teissig taught that the key was to capture the atmosphere of the film with a few visual elements, without too much text, too many faces or clues regarding the plot. It is also the reason for which the poster of the Italian film La Steppa (1962) by Alberto Lattuada, designed by Bedřich Dlouhý, with a fly on a branch, is among the most iconic of the Czech school of poster art.

In some cases the illustrators were selected directly by the filmmakers themselves, such as the artist and surrealist poet Eva Švankmajerová who was chosen by the director Věra Chytilová for the film Ovoce stromů rajských jíme (“The Fruit of Paradise”, 1970). If the name of the former rings a bell, it is because she is the wife and collaborator of the legendary surrealist animator Jan Švankmajer. For Chytilová, the delirious design of artist was particularly effective, combined with the “natural” style of the text, which was reminiscent of the opening credits of the film. Many of these artists were rewarded with significant international awards, such as the Prague-born Jaroslav Fišer (1919-2003), who received the Silver Hugo Award in 1976 at the International Film Festival of Chicago for his posters of Hra o jablko (“The Apple Game”), also directed by Věra Chytilová.

On the other hand, it should be emphasized that despite the freedom granted early on (and almost exclusively) to illustrators, in the years following the Russian invasion of 1968, the task of designing posters for foreign films in Czechoslovakia would become increasingly problematic. For a close-up of a hundred-dollar bill on the poster for 100 Rifles (1969), the master Zdeněk Ziegler was interrogated by the secret police, while Josef Vyleťal was forced to blur the American flag on his poster for Easy Rider (1969) with smoke.

On the other hand, it should be emphasized that despite the freedom granted early on (and almost exclusively) to illustrators, in the years following the Russian invasion of 1968, the task of designing posters for foreign films in Czechoslovakia would become increasingly problematic. For a close-up of a hundred-dollar bill on the poster for 100 Rifles (1969), the master Zdeněk Ziegler was interrogated by the secret police, while Josef Vyleťal was forced to blur the American flag on his poster for Easy Rider (1969) with smoke.

Today, the authors of these masterpieces of graphic art are gradually beginning to receive the attention they deserve. “Sight & Sound”, the historical British film magazine last May published an article of praise for the Czechoslovakian film posters, and the online shop “Terryho ponožky” specializes in selling historical posters. However, perhaps the real bible for fans is the book Czech Film Posters of the 20th Century, written by Marta Sylvestrová. A unique publication that displays hundreds of key examples, a wonderful book, the result of endless research, in which Sylvestrová covers the key years of the history of Czech film and the related production of posters, enriching it with fascinating anecdotes, and with the dazzling beauty of the works themselves.

The peculiar art of Czech posters for film could not survive the fall of communism, the logical consequences for the film industry and the rise of the Hollywood model. As a stereotype, you think of images of actors and company logo. We can rejoice however, in the fact that the rest of the world is finally discovering these masterpieces of graphics from the former Czechoslovakia.

by Lawrence Formisano