Tale of the concert in Prague in 1930 directed by the Maestro from Parma

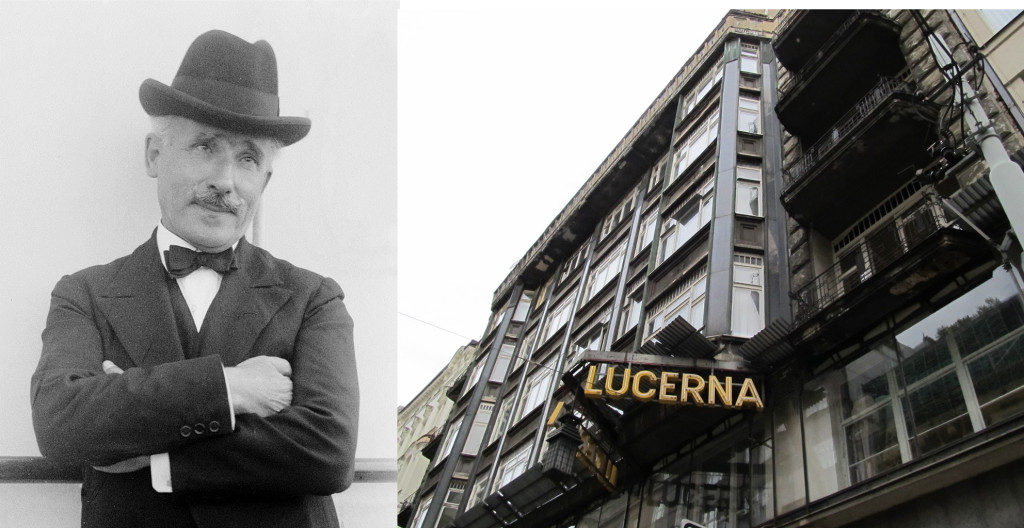

“Where is the producer? Where is the producer?”. The orchestra is silent. The Maestro yells furiously. It is May 23rd, 1930. In the Great Hall of the Praguian Lucerna Palace, Arturo Toscanini, the greatest, most controversial and the most brilliant conductor of the time is leading the rehearsals of the Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra of New York for an event concert, his first one, in the capital of the young Czechoslovak Republic. However, for him, an artist of the pure sound, obsessively demanding, the acoustics of the concert hall is an outrage and the morning rehearsal is a coarse dissonance. When Jaromír Žid, the organizer of the concert and one of the most important figures in the management of musical events in Czechoslovakia, came face to face with the Maestro of Parma, the choleric genius burst to no end. “How did you dare invite such an orchestra here?” Pressing further, he adds: “This is not a concert hall; it is a brewery at its most”.

Plain Toscanini style: the vehemence, the exigency, the perfection at all costs. As for the concert, it will be an entirely different story. We will come back to this later. In order to weight the success and the echo of that night at Lucerna, saved by the public and the charm of a masterful execution, it is mandatory to rewind the course of events. A few milestones of the life and career of one of the greatest conductors of all times are extremely useful to be acquainted with.

The star Toscanini emerged almost by chance, in 1885 in Rio de Janeiro. Being nineteen at the time and already a talented cellist, Toscanini got casted for a tour in Brazil. One June evening that made history due to an astonishing abandonment of the orchestra’s conductor, the young Toscanini, already a fine and encyclopedic melomaniac, was found to direct Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida. It was the first dramatic turn of events of his nearly 70 years long career. In front of the audience of Rio, he closed the score and began to direct the Verdian opera by heart. That night, under the Brazilian sky, Toscanini became distinct. It was his first time.

The star Toscanini emerged almost by chance, in 1885 in Rio de Janeiro. Being nineteen at the time and already a talented cellist, Toscanini got casted for a tour in Brazil. One June evening that made history due to an astonishing abandonment of the orchestra’s conductor, the young Toscanini, already a fine and encyclopedic melomaniac, was found to direct Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida. It was the first dramatic turn of events of his nearly 70 years long career. In front of the audience of Rio, he closed the score and began to direct the Verdian opera by heart. That night, under the Brazilian sky, Toscanini became distinct. It was his first time.

Once returned to Italy, his career was a succession of challenges and successes. He was first cellist at La Scala in Milan, where he met Giuseppe Verdi, whom he venerated both as a musician and as an individual. Then, from 1895, he became a permanent director of the Teatro Regio (Royal theatre) of Turin for a period of five years. Afterwards, he became director at La Scala and then came the American experience. During the First World War, the return was mandatory for a great patriot like himself. In 1917, he was able to conduct the military band on the Isonzo front under the enemy’s bombs. He turned music into a commitment, a weapon, and an ethic. Celebrated as the greatest revolutionary in the interpretation of classical music, Toscanini was also a proud antifascist, an artist opposing Mussolini and Hitler. But this is yet another story. Returning to the opera and stage, Toscanini is the one introducing the new theatrical concept of Wagnerian inspiration first in Torino and then in La Scala: darkness in the hall, the orchestral pit and no applauses. These circumstances became canonical but back then they rose criticism, the public seldom attacking him. He continued stubbornly on his own way. Brilliantly talented and disciplined, his performances soon became references to style and beauty.

A repertoire of classics, Beethoven, Puccini, Brahms but above all Verdi and Wagner, all in Toscanini’s style, always very faithful to the composer’s indications. Wagner’s family congratulated him on his extraordinary execution of Tristan and Isolde; Verdi did the same: he left a thank you note that the Maestro will be always carrying with him. This is Toscanini, a genius, a stubborn and a vehement man, but tormented by a constant unhappiness. “I am miserable, this stage is embittering me more than it does anybody else, and the problem is that on my turn I make other innocent ones bitter as well, unconsciously”.

The exigency that gives him grandiosity ruins him in the same time. Now, it is easy to imagine the rage of the great Maestro when in the Lucerna hall, built three floors underground and inaugurated ten years before, everything sounded horrendous. Him, the one accustomed to the most prestigious stages, to the purest sounds, him who for almost ten years, 1908-1915, had conducted the operas of the greatest composers, interpreted world premieres that made history in the Metropolitan Opera House in New York. And to think that the extraordinary Praguian concert hall, part of a complex designed by Václav Havel’s grandfather, was considered as one of the crowning glories of the early Czechoslovakian architecture.

Lucerna Palace, whose atmosphere and interiors are inspired from the New York art deco style of the 1920s, hosted since then artists like Ella Fitzgerald, Luis Armstrong and Ray Charles. Nevertheless, the acoustic presence of an orchestra accustomed to filling the great Opera houses of the world capitals was too much even for this astonishing hall of the aristocratic Prague of the beginning of the century. The marbles, the rich chandeliers and the mirrors do not stand up to the musical requirements of the great Maestro. But not even someone like Toscanini, able to shape music like a precious fabric, can influence “the circularity of the sound waves in the air”. The miracle, if it is indeed a miracle, was performed by the audience of that evening, the crowd in a moaning hall, the dense presence of the audience in a hall “submerged in the ground like a catacomb” and transformed the noise in melody. Thus, the article of May 24th, 1930 in Corriere della Sera ended up by celebrating “another triumphal evening” of the Maestro, cheerful counterpoint of the morning rehearsals’ catastrophe. “This very large Lucerna hall, deeply underground and cavernous as the cavity of a tympanum, seemed to possess the acoustic to exceed all records of the dreadful concert halls visited so far. This morning the horn sounds resembled those of trombones, and sound of strings seemed so full that they lost all their brightness”.

If the Toscanini present on the stage is famous for his harsh and precise gestures, the Maestro attending rehearsals is known for his verbal and physical vehemence. While preparing the opera he was fierce, yelling at his musicians, a prisoner of an unequaled anxiety for perfection. With his out of ordinary memory, he would never forget that day in Prague. And not even Žid, the producer, was able to forget it as even a few years later when Toscanini was conducting the Vienna Philharmonic he went to see the Maestro hoping to bring him back to Prague. “I can come to Prague, but to Lucerna surely not!”. End of the subject.

And despite all, the concert in Prague – one of the fifteen stages of a prestigious European tour that crossed cities like London, Paris, Vienna and Rome – was a great success of the public and an unparalleled musical event for the young Republic. At least three thousand people of the upper Praguian society of those times came to listen the sounds of the great names of classical German music: Beethoven, Wagner and Mendelssohn, among others. After all, a great part of the audience was speaking the language of Goethe: intellectuals and rich Jewish Praguian bourgeoisie of the 30s.

But Toscanini “who does not overlook things, wherever he would perform the best production when it is a production expressed with art in the musical language of the people”, as Corriere reports, also played the sweet, impetuous and touching notes of Vltava, a piece of the musical poem by Smetana, Má vlast (My Country). As expected, the notes of the great Czech composer, that opened the second part of the concert, stirred the audience that could not withhold the applauses.

Among them, in the dignitary stand, was the first President of Czechoslovakia Tomáš Masaryk, great intellectual and man of letters. The beginning of the concert was postponed by half an hour, to eight o’clock precisely for him. He did not want to miss a single note from the great Italian Maestro and so it was for almost two minutes. Once the President entered the hall, Toscanini opened the great remedied journey at Lucerna. Which closed with an audience in euphoria and Masaryk standing and applauding the genius of the Italian director. Able to shine even in this astonishing, underground, disharmonic “brewery”.

by Edoardo Malvenuti