Among the events organized in the European Capital of Culture of 2015 the exhibition dedicated to the “Walt Disney of the East”, Jiří Trnka, stands out

Plzeň is known worldwide for the world-famous Pilsner Urquell, but there are many famous names associated with the city. The first that spring to mind might be Emil Škoda, Karel Gott or Petr Čech. From an artistic point of view, however, there is a figure who towers over the others, that of Jiří Trnka, the illustrator, animator and director. It is therefore no surprise that Plzeň, European Capital of Culture 2015, has devoted a major exhibition to the artist in recent months.

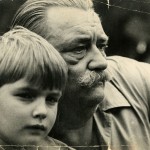

An eccentric, larger than life personality, long moustache and imposing presence, the great Bohemian director, animator and set designer was born on February 24, 1912 in Plzeň, where he would spend all his childhood and where he would discover his raison d’être – the art of the puppeteering. Trnka first learnt the trade by observing his grandmother, who manufactured and sold dolls, but began to form professionally when he attended the school of the puppeteer Josef Skupa, one of the greatest in his homeland. Skupa immediately noticed the talent of the Bohemian and gave him a job as an assistant, teaching him to sculpt, dress and manoeuvre the puppets. In a difficult period for the Trnka family economically, it was Skupa who persuaded the boy’s parents to allow him to be able to follow his inclinations and develop his skills by attending the School of Applied Arts in Prague. From 1936 Jiří worked as a set designer and book illustrator, but his heart remained with puppets, which in later years would come to life in his hands, displaying their own feelings and thoughts.

With the arrival of the effervescent climate following the war, the director approached the world of cinema. After founding the study Bratři v triku (Brothers in t-shirts) with Eduard Hofman and Jiří Brdečka, in which many illustrators and directors formed later, the animator was able, within a time frame of one year, to create five animated short films. Among the most memorable were Zasadil dědek řepu (Grandfather planted a beet), Zvířátka a Petrovští (Animals and robbers) and Pérák a SS (The Springer and the SS men). Evidently, the phase of the long apprenticeship was over, and the true Jiří Trnka was born, now ready to create his own masterpieces.

We return to the present, and to his hometown, where seventy years after his film debut, the magnificent exhibition “Atelier Jiří Trnka” is organized with the help of his son, Jan, and running until 10 May at the Gallery of the City of Plzeň. With dozens of props, drawings and objects, among the aims of the initiative was to show that the output of the artist was not limited exclusively to the world of cinema. The Bohemian was also active in theatre, he illustrated books, painted and sculpted. The exhibition, a collection of 300 small creations, spans from his early years in Plzeň, to the final ones in Prague, where he made friends with important figures of the cultural life of the time, such as the actor/playwright Jan Werich and the aforementioned Jiří Brdečka. Among the many objects of interest, one must highlight the very first puppets of young Trnka, the “Kinoautomat” with a selection of the most magical scenes from his films, and an interactive part where the audience has the opportunity to take on the role of the director and create stop motion animation, a technique for which Trnka became famous.

We take another leap into the past, to the year 1946, when the animator wins a prize at the Cannes Film Festival for the short film Zvířátka a Petrovští, thanks to the lyrical style of the fairytale and the beautiful music that accompanies it. Many consider this film as the work that brought an end to the monopoly of Disney in the world of animation, in addition to forming the real roots of the genre in Europe. Later, the director would deal with more complex subjects, producing films with more prickly traits, as in Dárek (The Gift, 1946), a very personal satire on bourgeois values in a style that evokes surrealism. Despite the great reception, the director is not satisfied with traditional animation, which he believes requires the involvement of too many intermediaries, and so, with the help of puppeteer Břetislav Pojar, he begins to experiment with puppets.

We take another leap into the past, to the year 1946, when the animator wins a prize at the Cannes Film Festival for the short film Zvířátka a Petrovští, thanks to the lyrical style of the fairytale and the beautiful music that accompanies it. Many consider this film as the work that brought an end to the monopoly of Disney in the world of animation, in addition to forming the real roots of the genre in Europe. Later, the director would deal with more complex subjects, producing films with more prickly traits, as in Dárek (The Gift, 1946), a very personal satire on bourgeois values in a style that evokes surrealism. Despite the great reception, the director is not satisfied with traditional animation, which he believes requires the involvement of too many intermediaries, and so, with the help of puppeteer Břetislav Pojar, he begins to experiment with puppets.

If the other great Czechoslovak animator of the era, his compatriot Karel Zeman, was dubbed “the Czech George Méliès”, and took his inspiration both from the illusionist French and the adventure novels of Jules Verne, Trnka has always used folklore and the national history of his country as the origin of much of his work. In 1947 he entered a new artistic path with the feature film Špalíček, known abroad as The Czech Year, which brought his experience as a puppeteer to film, and began to exploit the potential of editing. The film consists of six stories about the legends and traditions of his homeland like the typical carnival (Masopust) or the legend of St. Procopius (Legenda o svatém Prokopu). Subsequently he alternated between adaptations of Czech stories, such as Bajaja (1950), based on the tales of Božena Němcová, foreign tales, such as in Císařův Slavík (1948, The Emperor’s Nightingale). In the latter, a work inspired by Hans Christian Andersen, he reaches the peak of his poetry by mixing realism and surrealism to a unique effect.

Following his adaptation of “The Good Soldier Švejk” by Jaroslav Hašek (1955), Trnka made one of his most ambitious films, the cinematic adaptation of William Shakespeare with Sen noci svatojánské (1959; A Midsummer Night’s Dream). Although it remains a film that divides the audience, it was very successful abroad and induced an English critic to nickname the director “Walt Disney of the East”. It is indeed a nickname which is still in use, but it should be emphasized that, in hindsight, the comparison with the American cultural icon seems increasingly misleading and inappropriate. Disney was also an entrepreneur and a business magnate, and his films aimed primarily at an audience of children. Trnka was purely an artist, who made films for all ages, but perhaps especially for adults, and it was important for him to maintain his national identity and even when he drew inspiration from other sources.

Even for his son Jan, the films of his father were more sophisticated and emotional. “My father never identified with Disney’s approach to animation and the kitsch style of his characterizations. However, he always held him in high regard”, said the director who now dedicates his time to safeguarding the legacy of his father, and to the restoration of his works. The best example of this refinement, which distinguishes Jiří Trnka from other animators, can be found in his final work – the short Ruka (The Hand, 1965). A manifesto for artistic freedom, Ruka tells us the fate of a potter and sculptor who from a huge hand, receives the order to model a large monument dedicated to it. The artist repeatedly refuses, and having attempted to offer gifts and money to bribe him, the hand resorts to violence. The potter is forced to obey, and having been locked in a cage, he sculpts a marble hand. The prophetic short film, made four years before the death of the filmmaker, but also three years before the Russian occupation of his country, and the end of the proposed reforms of Alexander Dubček during the Prague Spring, could be considered the definitive allegory about the role of the artist who toils hard in an authoritarian regime. The work is perhaps the crowning achievement of the master of animation who today, with this exhibition, is justly celebrated in his hometown.

by Lawrence Formisano