The most iconic (musically and politically) among Czechoslovak rock bands marks their 50 years of activity

The Plastic People of the Universe (also known as Plastici or PPU) were one of the most well-known groups beyond the curtain even before 1989. This is also despite a not exactly simple musical style, certainly much less than the likes of the Hungarians of Oméga and of Polish Dezerter. Not only that, those who have ever been to the Vagon in Národní třída, will also know how the Plastics look, since the faces of some of them are displayed on the walls alongside the likes of Morrison, Zappa, Lennon & co. What has created their myth, if the PPU records are anything but simple? The swift reply: during normalization, they were imprisoned due to their music and this turned them into a symbol of dissent.

Now, you would expect a symbolic group of dissidents to have been founded with the best intentions during the Prague spring, and that after the Soviet occupation they chose to go underground to protest. The reality is quite different.

The Plastici were founded exactly during the month following the invasion of the sister nations of the Warsaw Pact. A central member was, and would remain so until the end of his days, Milan ‘Mejla’ Hlavsa, a bassist and singer with a voice that would be a euphemism to call ungraceful. Around him, in the early years, a large number of musicians would rotate, and not just for reasons involving cages. Their intent was anything but to become standard bearers for protest.

The will of the band, quite simply, was to make slightly little different music. There were two primary examples to follow: Frank Zappa, and in fact “Plastic people” is a song of his, and Velvet underground, so much so that just like them they would immediately get a manager. This was Ivan Martin Jirous, a strange critic and art historian who was supposed to be the equivalent of Andy Warhol in theory but who in stormy ways was very close to a Malcolm McLaren without the marketing skills. In fact, being prone to continuous outbursts he would be nicknamed Magor (nutcase) and in later years he would be more inside than out.

The Plastics in that 1968, like a good group that did not want a hassle with the regime, asked to be registered as a band with the competent authority. However, the request was rejected because “their music is morbid and they have long hair”. What does it mean to be rejected? It was soon said.

The Plastics in that 1968, like a good group that did not want a hassle with the regime, asked to be registered as a band with the competent authority. However, the request was rejected because “their music is morbid and they have long hair”. What does it mean to be rejected? It was soon said.

In the Western world, everyone starts off as a street artist and to achieve success there is a lot of work to do. Everything is simpler in a socialist country. If the application to register is accepted, the State gives you money to become an artist. If it is rejected, you become a street artist, you cannot play and the State also regains the instruments (which are normally assigned, not purchased). On that occasion, Magor, who “understood about politics”, easily reassured Hlavsa by saying that this situation of strict controls would last at most five years and that the band could easily survive such a short period.

“Apart from the fact that he was wrong by twenty years, Jirous was also right: in the underground we managed very well”, Hlavsa would say after 1989.

We are in a socialist regime, however. So, even if the state doesn’t pay you to play, it still continues to give you money but to do something else. In Hlavsa’s case, money was provided for him to be a butcher. To Josef Janíček, a keyboardist who joined soon after the foundation, it was to work as a mechanic. And Janíček with spare parts managed to put together amplifiers. The instruments were probably made with the Brian May method, that is putting together the pieces of other instruments found going around the landfills.

At the beginning of the 70s the formation of the band began to become stable: in addition to Hlavsa and Janíček, Jiří Kabeš (viola) also joined, and Paul Wilson, a Canadian (because at that time the Plastici sang also in English) which would prove to be useful some years later. In this period, the collaboration began with Egon Bondy, who became the main author of their texts. Bondy, born Zbyněk Fišer, was a strange animal, a bit like anybody else hanging around the PPUs. During his life he has in fact collaborated with the VB (the police of that time), only to be excluded from this collaboration, on several recurring occasions, for his ideas… too far left. In the early 1970s he had a profound fascination with the Maoist Cultural Revolution and his works of that period made him a rare case of “leftist dissident”. His most important work is “The Invalid siblings” and is set in a very distant future, but it is a metaphor for how non-state artists lived in that Czechoslovakia.

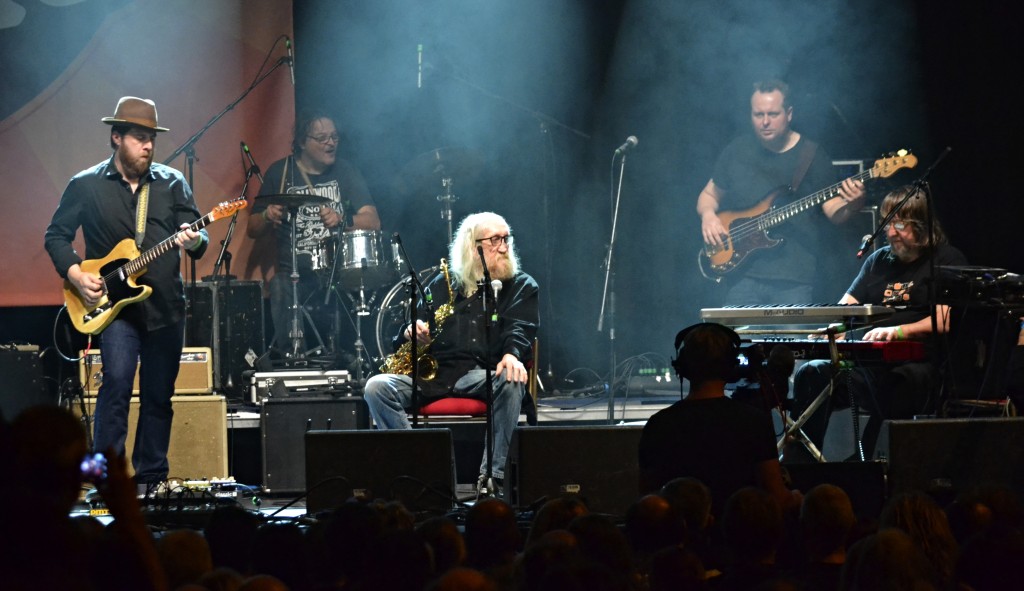

In 1974 the last piece of the historical formation of Plastic was added, namely the saxophonist Vratislav Brabenec, and joined on the condition that the group would no longer use texts in English. At that time the band regained the status of a “state band” for a good two weeks! Then the license was revoked because the Plastics still did not want to cut their hair and or do anything like that. In this period they also release a studio album (recorded in a castle not far from Prague) which was added to the numerous live recordings of previous years.

Wasn’t it said that the Plastici couldn’t play? As a matter of fact, officially they could not, but already in 1969 they had arranged it as they could. They played at friends’ houses, at friends’ weddings, at friends’ funerals, and yes, the PPUs also played in a cemetery, but above all in the countryside where hundreds of people arrived by word of mouth. Not that these concerts always went smoothly, in fact often the VB lead a blitz, the most famous one remains the one in 1974 near České Budějovice. The VB arrested over a thousand people even before the Plastici started to play (Led Zeppelin played at least 20 minutes at Vigorelli stadium).

In response, Jirous decided to organize the so-called “second culture festivals”. Then, in 1976, the police decided to act in a more focused manner than usual and set out to get Jirous, Hlavsa & co. one by one at home. Plastic members in the best of cases earned eight months in jail (Jirous would continue to go in and out until the end of socialism), all the recordings and books found during the blitz were seized. Above all, Paul Wilson was expelled from Czechoslovakia and this was a turning point. Wilson in fact, through diplomatic channels, managed to bring live recordings abroad and even those from the studio album, which today we know with the name of Egon Bondy’s happy hearts club banned (banned, not band).

Now that the material was published abroad, it was necessary to make the Plastics famous overseas. It would be a young theatre writer with a French “r” who would take care of this, who had met the band a couple of years before. He would give way to an initiative to denounce the violations of human rights in Czechoslovakia (exemplified precisely by the arrest of the PPUs). The writer in question is obviously Václav Havel, and the initiative was Charta 77. The main result was that Havel would reach Magor behind bars and he would also have to wait several years to get out.

The Plastics, on the other hand, in 1978 were already free as birds. Their activity quietly continued until 1987 when Hlavsa, fed up with the bulky moniker, founded Půlnoc together with Janíček and Kabeš. The Velvet Revolution arrived, and in 1991 Půlnoc released City of Hysteria (similar in sound to Egon Bondy’s but less complex) for… Arista Records! The band, a more unique than rare case, probably due to the popularity in political dissent, managed to publish for a major label.

The Plastici would reform in 1997, after warm invitations from Havel, with the historical formation of Hlavsa-Brabenec-Kabeš-Janíček. In addition to the original line-up, Jan Brabec, who had already been their drummer, and Josef Karafiát on guitar would join. Because maybe you didn’t notice, but until then there had never been any talk of guitarists. The Plastics in fact, had never had anyone officially filling the role (and during the studio recordings the six strings were handled by Hlavsa).

Ironically, with this “new golden-lineup”, the Plastici would only play until 2001, when a cancer took the life of Hlavsa. Nevertheless, they were to continue playing until 2015, when the desire for the West that has always permeated them, made them definitively identical to many old rock dinosaurs. The Plastics, now also seventy-year-old dinosaurs, broke up. They did it in the worst way, with two new groups and legal battles about which of the two complexes bore the right to the name. For now the “real” Plastics are those in which Janíček and Brabenec have remained; those of Kabeš and Karafiát are called PPU New Generation. Both are active live, even if this strange “final with a bang” leaves a very bitter taste in the mouth and the belief that the PPU story must find a better conclusion.

by Tiziano Marasco