Thousands of questions remain following the response from the ballot boxes, with a notable reshaping of the traditional parties and exploits of the protest and populist votes. The tycoon Andrej Babiš is a new protagonist of Czech politics

The early elections for the Chamber of deputies, which took place on the 25th and 26th of October, quite predictably left more doubts than guarantees as to what Prague’s future government will be, and especially regarding which program they will follow.

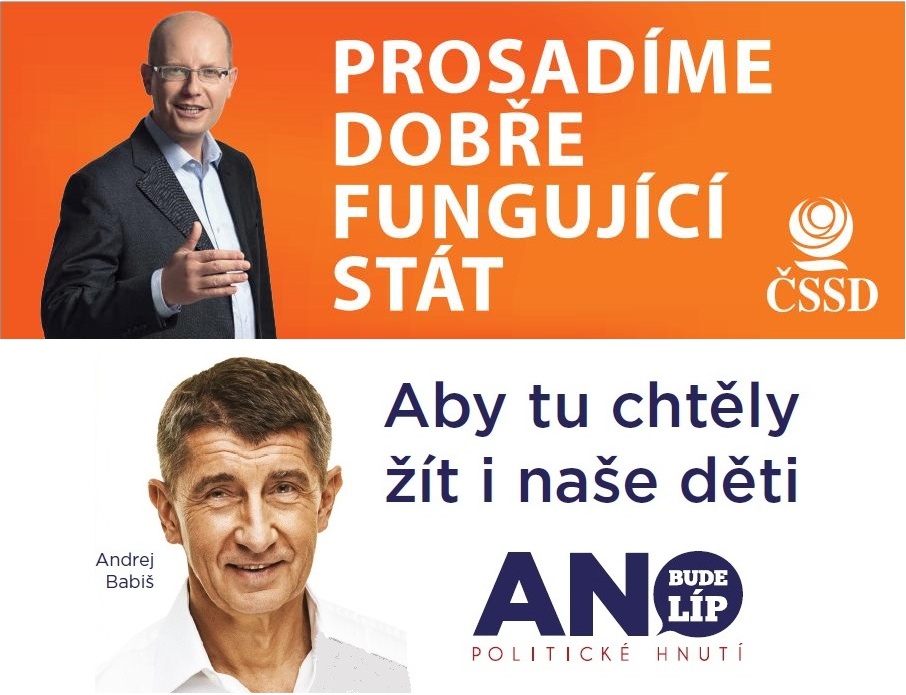

Among the various unknown factors, one thing however remains clear: for the formation of the next executive branch, we won’t be able to overlook the billionaire Andrej Babiš, who whilst leading his Ano 2011 movement (the name of which means Yes in Czech, and in this case is the acronym of Akce nespokojených občanů, Action of Dissatisfied Citizens), managed to gain 19% of the votes and 47 deputies, out of a total of 200.

The “Berlusconi” of the Czech Republic”, or rather “Babišconi”, as some have begun to call him, 59 years of age and of Slovak origin, is one of Central Europe’s richest men, and now leads an agro industrial and chemical empire, consisting of 200 companies and valued at almost 100 billion crowns (around 4 million euros) and almost three million employees. Babiš promises to reform the state by applying, as he states, the same principles with which he manages his companies, and making his principles of social unity count, improving the pensions of the elderly while at the same time not increasing taxes, but just improving the system of collecting money due. Regarding employment, Babiš is even more direct when explaining his remedy: “trust in me, since I have already created so many new jobs”. They are indeed promises which have convinced many voters, to the extent that during the counting of the votes at some point it even seemed they could threaten the ČSSD Social-democrats’ first position among the parties.

The most disappointed party with the results are actually the Social Democrats, who were incapable of reaching more than a measly 20.5% of the votes, a result which was well away from the 30% they were aiming for, and it means a goodbye to the planned ČSSD one-party government, with external support from the non-reformed communists of the KSČM.

The most disappointed party with the results are actually the Social Democrats, who were incapable of reaching more than a measly 20.5% of the votes, a result which was well away from the 30% they were aiming for, and it means a goodbye to the planned ČSSD one-party government, with external support from the non-reformed communists of the KSČM.

This latter party on the other hand, openly nostalgic about the pre-1989 regime, managed to reinforce its traditional strong core, by gaining 15% of votes and 33 deputies (seven more than in 2010).

The acceptance of the communists was particularly apparent in the areas most affected by unemployment and social unease, especially in the coal crisis areas and the steel industry of northern Moravia, where the unemployment figures are almost reaching 15%.

The geographical distribution of the votes once again shows the discrepancy that exists in the Czech Republic, between the capital and the rest of the country. Prague almost consists of a state within a state, an island of well-being, with much less unemployment (a little more than 4%, whereas the national average is close to 8%), average salaries of almost 33,000 crowns a month (around 1300 euros, compared to a national average which does not even reach 25,000 crowns) and an overall standard of living which is considerably higher than the EU average. In the area of Prague, where a little more than a million of the ten million inhabitants of the Czech Republic reside, it is calculated that the GDP per capita is 70% higher than the EU average (according to Eurostat). At a Czech national level, it only reaches 80% of the EU average. A discrepancy, which when scrutinizing the statistics, you even reflect on the life expectancy of inhabitants which in the capital reaches almost 80 years, nearly five more than in the poorer regions, which have to deal with environmental problems.

It is no coincidence that in Prague, the top party is the conservative Top 09, the alliance guided by the prince Karel Scwarzenberg, who gained 23% of the votes in the capital, compared to a meager 12% nationally. The old, charismatic aristocrat, who was seen dressed in a tuxedo as agent 007 in manifestos, dedicated to facing the risk of modern communism, was clearly very convincing in the rich, western Prague, though a lot less so in Ostrava and its surroundings, in north Moravia, where thousands of miners and workers risked losing their job and where the cuts on welfare benefits wanted by the previous centre-right government played a strong role.

A huge debacle however, faces the Civic Democratic Party, the historical powerhouse of the Czech right, who managed to elect just 16 deputies (37 less than the previous legislature), having been devastated by scandals and the rigid politics of austerity backed by the government in recent years.

Two other parties managed to exceed the 5% barrier. The Úsvit (Dawn), another clearly populist political party, led by Tomio Okamura, a Czech of Japanese origin, and enlivened by a rhetoric based on pleas to direct democracy, to the wide use of the referendum and the fight against corruption. Finally, also the Christian and Democratic Union, the KDU-ČSL, who return to the chamber after having skipped a legislature.

Given the figures displayed and the mosaic/stew consisting of seven parties now represented in the chamber, the most feasible solution for the government from the beginning, has seemed to be a centre-left majority of three parties. It should be the Socialdemocrats, the Ano 2011 of Babiš, and the Christian Democrats of KDU-ČSL who form it.

It would however, be a coalition with a yet undefined political agenda, and one with a big question mark over who will be the Prime Minister.

Regarding his political program the greatest stumbling block concerns taxes, given that Babiš has promised not to increase them, while the Social-democrats want to do the opposite with both the more well-off citizens and the big businesses (starting off with the energy, financial and telecommunication companies).

Another delicate topic is the return of goods and property, which were nationalized during the pre-1989 regime, to the church. The Social Democrats are asking for a revision of the recently approved law, and a decrease in the financial compensation planned, which they consider to be too generous in favour of the church. Babiš and his movement, also do not appear to have warmed to this law, and already seem ready to back a revision of the legislation.

The Christian Democrats, obviously closer to the Catholic Church, are of the opposite opinion, even to the extent that some KDU-ČSL members declared “for us the case is closed. Bringing the matter up again would make us a banana republic”.

The fusion of the three parties does not appear to be stable even when discussing European policies, with the presupposition however, that the topic has remained in the background during most of the electoral campaign, having been disregarded by the political leaders, and visibly heard very little by the constituency.

The Social Democrats on the other hand, appear to be closer to Brussels, having supported the need to sign the accession to the Fiscal Compact. So far only Prague and London have refused to do so. In the times of the Eurozone crisis, the ČSSD have been more cautious towards a future acceptance of the single European currency, which in their opinion cannot take place before 2020. Their position is shared with the Christian Democrats.

The stance of Babiš regarding the Union on the other hand is yet to be determined. In the electoral program, the need of the Czech Republic to become a “serious and trustworthy partner to Brussels”, was underlined, as was his intention to consolidate the Czech participation in the EU. Babiš himself, does not hide the fact he considers any more intense form of integration into the EU states to be unacceptable. “The fiscal compact damages our national sovereignty”, he said, without also failing to show his opposition towards the system of bank surveillance, “which are not necessary as the lending institutions of the Czech Republic operate in a correct manner”.

His aversion towards plans to enter the Eurozone is rather clearer, “I know what I am saying, as I, with my group of companies, am the fourth exporter of my country and I have been doing business with foreigners for a lifetime. The Czech crown is an indispensable instrument to stimulate our economy and defend our exports. So we will not even talk about the Czech Republic entering the Eurozone”.

The responsibility, should no surprises occur, will go to Bohuslav Sobotka, the Social Democrat leader, despite being notoriously unpopular with the Head of the State Miloš Zeman. It must be said that his quotations, after the disappointing electoral result, seemed to be falling drastically. Sobotka however, had the force to resist the attacks directed at him by his party members, in particular by the “coups” led by the ambitious Michal Hašek (the governor of southern Moravia and the vice-president of ČSSD), instigated by the head of state Zeman, himself.

Sobotka is most likely to be destined to come out as the winner when the scores are settled within the Social-democratic party. However, one question mark remains: what stability could such a battered party as the Social Democrats offer to the government?

Babiš, from his point of view, has already declared to be in agreement, by and large, with a planned alliance between the Čssd and the KDU-ČSL, and a government led by Sobotka, but he has also booked a place in the front row in the future executive. “I’ll dedicate myself to the Ministry of Finance, in order to correct all the mistakes made by the previous government”, he states.

Anyway, Babiš has categorically excluded a government collaboration with the communists, as with the ODS and the Top 09, two parties which he defined as the “symbol of the corruption in the country”.

Meanwhile, to consolidate his image as a clone of Berlusconi, Babiš just a few days before the voting, made a big splash in the media market by buying two of the most read newspapers of the country, Mlada Fronta Dnes and Lidové Noviny, while announcing his intention to form the country’s main publishing group within the next four years. “It’s because I consider it convenient from a business point of view, and because I am counting on getting profits from it, but certainly not because it will help me in politics” he said.

The next move regarding the government is in Miloš Zeman’s hands, being a veteran of the left and an old fox in politics, who has the responsibility of naming the next Prime Minister. The policy making creativity with which Zeman employs his presidential powers is well known and one cannot exclude, in such an unclear situation, that further surprises or solutions may arise in the presidential arena.

Other observers even consider it possible that the current government led by economist Jiří Rusnok and wanted by Zeman last summer could continue, despite being dubbed “the government of the friends of the President”, as the critics call it.

by Giovanni Usai