On June 28 will be the centenary of the assassination of Franz Ferdinand. The links with history and literature, a duchess and a good soldier, strongly intertwined with the Czech nation

Meanwhile, in the geographical region which opposed the former empire, the Czech Republic prepares for the anniversary with an extensive, organized series of events

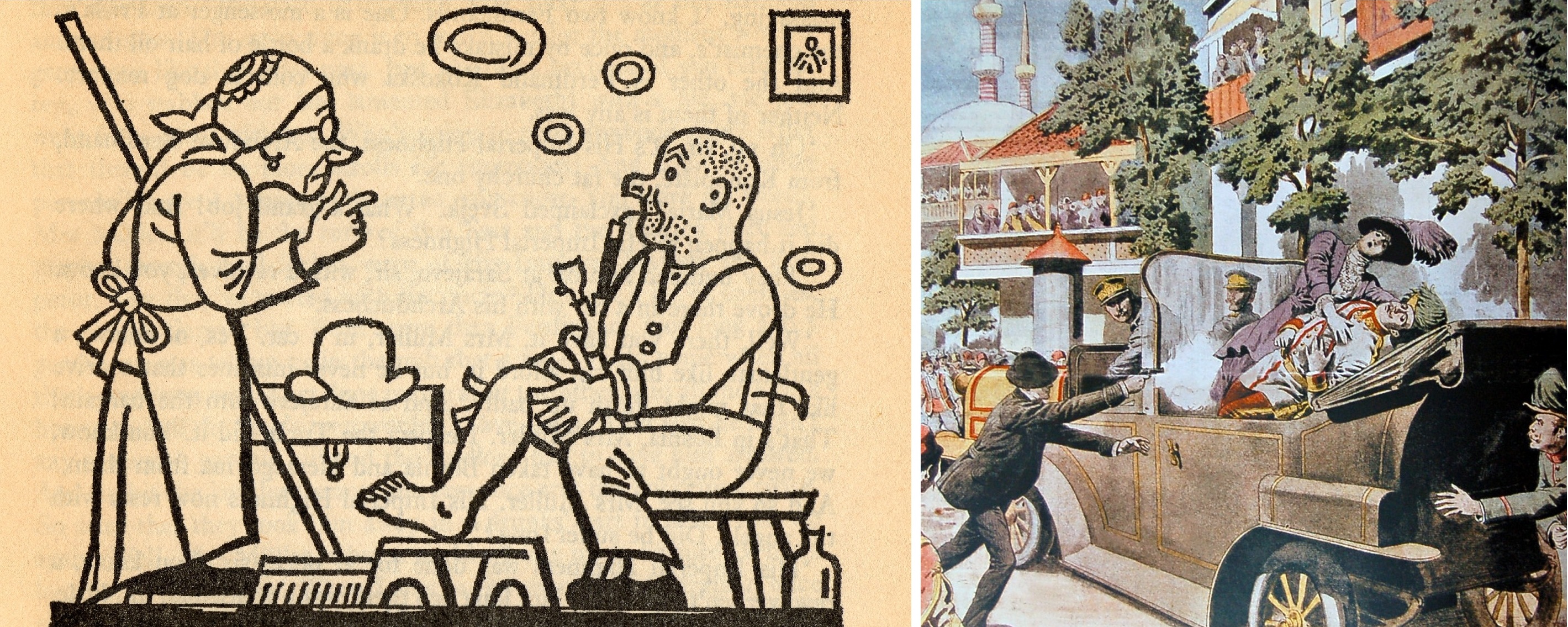

“And so they’ve killed our Ferdinand”, said the charwoman to Mr Švejk… This is the most famous incipit of Czech popular literature, the arrival in the “Hašekian” Prague of the news that shook the whole world, the spark that ignited the Great War and which within a few pages, sent the good Soldier Švejk to the frontline. Which Ferdinand? The governess asks to clarify, in the author’s irreverence: “Oh no, sir, it is His Imperial Highness, the Archduke Ferdinand, from Konopiště, the fat churchy one”. The attentive reader knows that Konopiště is a town in central Bohemia, and it is perhaps already curious to know which, and how many ties with the current Czech Republic, some famous and some not, there are in this story. The first and most obvious one, that at the end of the war the First Czechoslovak Republic was born.

First things first. On 28 June 1914, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was visiting Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. It was the southernmost province of the empire, torn from Ottoman rule in 1878. On June 28 was the anniversary of the agreement between the Archduke and his uncle, Emperor Franz Joseph, who permitted him to marry Sophie on the condition that it would be a morganatic marriage, thus refusing to make her an empress. Sophie Chotek von Chotkowa, Duchess of Hohenberg, of a Bohemian family from the region of Plzeň (born as, Žofie Chotková), was in fact of a lower class than the one chosen for the throne of Austria: she had no choice but to give in. It is said that their first meeting was at a dance gala in Prague, but what is certain, is that they got married in the castle of Zákupy, northern Bohemia, in July 1900. The Archduke felt more at ease in the Bohemian province than in the Viennese capital, and shortly before his ill-fated last trip, he changed his residence to the castle of Konopiště. Between June 12 and June 14, 1914 they hosted the Kaiser Wilhelm II, according to the Austrian press, to show him the beautiful rose garden. Actually, in that garden there were no roses at all; in the prospect of a future war they discussed their distrust of Italy (technically an ally), as well as how to go on without it.

First things first. On 28 June 1914, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was visiting Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. It was the southernmost province of the empire, torn from Ottoman rule in 1878. On June 28 was the anniversary of the agreement between the Archduke and his uncle, Emperor Franz Joseph, who permitted him to marry Sophie on the condition that it would be a morganatic marriage, thus refusing to make her an empress. Sophie Chotek von Chotkowa, Duchess of Hohenberg, of a Bohemian family from the region of Plzeň (born as, Žofie Chotková), was in fact of a lower class than the one chosen for the throne of Austria: she had no choice but to give in. It is said that their first meeting was at a dance gala in Prague, but what is certain, is that they got married in the castle of Zákupy, northern Bohemia, in July 1900. The Archduke felt more at ease in the Bohemian province than in the Viennese capital, and shortly before his ill-fated last trip, he changed his residence to the castle of Konopiště. Between June 12 and June 14, 1914 they hosted the Kaiser Wilhelm II, according to the Austrian press, to show him the beautiful rose garden. Actually, in that garden there were no roses at all; in the prospect of a future war they discussed their distrust of Italy (technically an ally), as well as how to go on without it.

Whether an unforgivable oversight or frightening affront, June 28, the day of Saint Vitus in the Orthodox calendar, is also the anniversary of the Battle of Blackbird’s field of Kosovo (or Kosovo Polje) of 1389, bitterly fought between Serbs and Ottomans. It was the last great battle before the Turks returned to the Balkans, now a Serbian national holiday, and in 1914 Serbia was a proud nation and a new state. From the mid nineteenth century, driven by the nationalism that inflamed Europe, the idea of a nation of the Southern Slavs (Yugoslavia) was gaining increasing ground, and Serbia was in fact the greatest supporter. A nation that rebelled against Austria-Hungary as they had done against the Turks.

Franz Ferdinand and Sophie went through Sarajevo in mid morning, sitting in the back of a car in a motorcade involving seven. Seven was also the number of the young assassins of the group Young Bosnia (Mlada Bosna), spread out along the road that ran along the Miljacka, the small river that runs through the city. Young and inexperienced, the attack risked becoming a farce: there were one who arrived late, one who escaped, one who got swallowed up by the crowd. A bomb was thrown, but missed its target creating havoc and wounding people far from the Archduke. The holiday however, was ruined, and the couple decided to interrupt the parade and go the hospital. They therefore warned the driver, a certain Leopold Lojka from Znojmo (Moravia), that he was on the wrong path: to backtrack and change direction. Gavrilo Princip, not quite twenty years old with a revolver in his pocket, after the first explosion abandoned the plan to get a coffee, happened to see the Archduke’s car slowly move few metres away. Not believing his eyes, he jumped out of his chair and fired his shots. “Seven pips like in Sarajevo!” (actually it took only two) as an ill-fated card playing friend of Švejk exclaimed, before being arrested, but above all would become one of the most frequently used quotes in the Prague taverns (Sedm kulí jako v Sarajevu, and the host is ready with seven shots of slivovice). Princip’s intention was to assassinate the Archduke and the governor Potiorek, but the latter saved himself, sadly at the expense of the Duchess Sophie (legend has it that she was expecting a fifth child, but this seems to be indeed, a legend). The die had been cast, the imperial wrath was strong, the accusations were directed towards Serbia, and in a month’s time the most devastating war ever imagined (but we know it would be overtaken) flared in the trenches all over the world. The young regicide, claimed to have done it in the name of Yugoslavia, thus ensuring there was no proof of a Serbian coup, but after a decade of calling to arms in Europe there was no interest in minor trifles.

The assassin Princip was captured and transferred to the prison in Terezín, which is again in the current Czech Republic, in the region of Ústí nad Labem, where he died of tuberculosis in 1918. The same fortress would sadly end up being used by the Nazis to make a concentration camp. Regarding the Moravian driver Leopold, the survivor, he was given the task of sending three telegrams: one to the Emperor Franz Joseph, one for the German Emperor Wilhelm II, and one for the oldest child of Franz Ferdinand. Having been rewarded for his heroic service in 1916, for the last ruler of the Habsburg Empire, Charles I of Austria or Charles IV of Hungary (the heraldry depends on one’s of point of view) he used the 400 thousand crowns to open a hotel in Brno, showing customers a bracelet of Sophie and the bloody braces of the Archduke.

The assassin Princip was captured and transferred to the prison in Terezín, which is again in the current Czech Republic, in the region of Ústí nad Labem, where he died of tuberculosis in 1918. The same fortress would sadly end up being used by the Nazis to make a concentration camp. Regarding the Moravian driver Leopold, the survivor, he was given the task of sending three telegrams: one to the Emperor Franz Joseph, one for the German Emperor Wilhelm II, and one for the oldest child of Franz Ferdinand. Having been rewarded for his heroic service in 1916, for the last ruler of the Habsburg Empire, Charles I of Austria or Charles IV of Hungary (the heraldry depends on one’s of point of view) he used the 400 thousand crowns to open a hotel in Brno, showing customers a bracelet of Sophie and the bloody braces of the Archduke.

The Sarajevo of today is like a construction site exhausted by the big summer celebrations. At the entrance of the oldest bridge over the Miljacka, the Latin bridge, there is an intersection where the attack took place, precisely at the point where the Ottoman old city gives way to the buildings of Austrian influence. A plaque tells of the episode in Bosnian and English, on the facade of the city museum still hidden away by the repair work. A young tour guide tells a stream of Japanese visitors how and where the driver from the Czech Republic (displaying a certain historical nonchalance) slowly maneuvered the old Gräf & Stift limousine, now on display at the military museum in Vienna. Inside the museum, we look at a photo exhibition, two wax statues of the murdered victims and the merciless decline of Gavrilo Princip from national hero (at the time of socialism) to international terrorist (in today’s world). Franz and Sophie wink at us in the town centre in the form of hostel names, restaurants and tearooms, in the predictable souvenirs.

Meanwhile, in the region geographically opposed to the former empire, the Czech Republic prepares for the anniversary with a vast, organized series of events: Velká Válka, the Great War. Exhibitions and initiatives throughout the whole summer, to highlight the impact on Czech and world history, the call to arms of the Bohemians and Moravians, the dissolution of Austria-Hungary and the arrival of the freedom that they dreamed of during the imperial rule (a slightly slackened rule for today’s standards), the discreet charm of the Bohemian nobility on the contemporary Czechs. Eight major museums are part of the project, the Prague National Technical Museum, the Postal Museum and the Institute of Military History, and in Brno the City Museum, the Technical Museum and the Moravian Museum and Gallery, while in the castle of Konopiště, the bullet that pierced the archduke has been displayed. This is not to say there will be no similar ventures even in smaller towns, for example in the Krkonošské muzeum of Jilemnice, which tells of the dynasty of the Harrachs, their exponents and friends of Franz Ferdinand, so much so that the Count Franz Harrach travelled with the archduke in Sarajevo and “lent” him the aforementioned driver Leopold.

We can therefore expect a summer full of history and overloaded with dark terminology, full of words such as attack, war, murder and lost noblemen, while hoping that the good humour of Švejk can make the satire against the war and against simple glorification, efficient and immortal, as intended by his burlesque author.

by Giuseppe Picheca – from Sarajevo