The adventures of the good soldier, born from the imagination of Jaroslav Hašek, remain an essential part of Czech popular culture

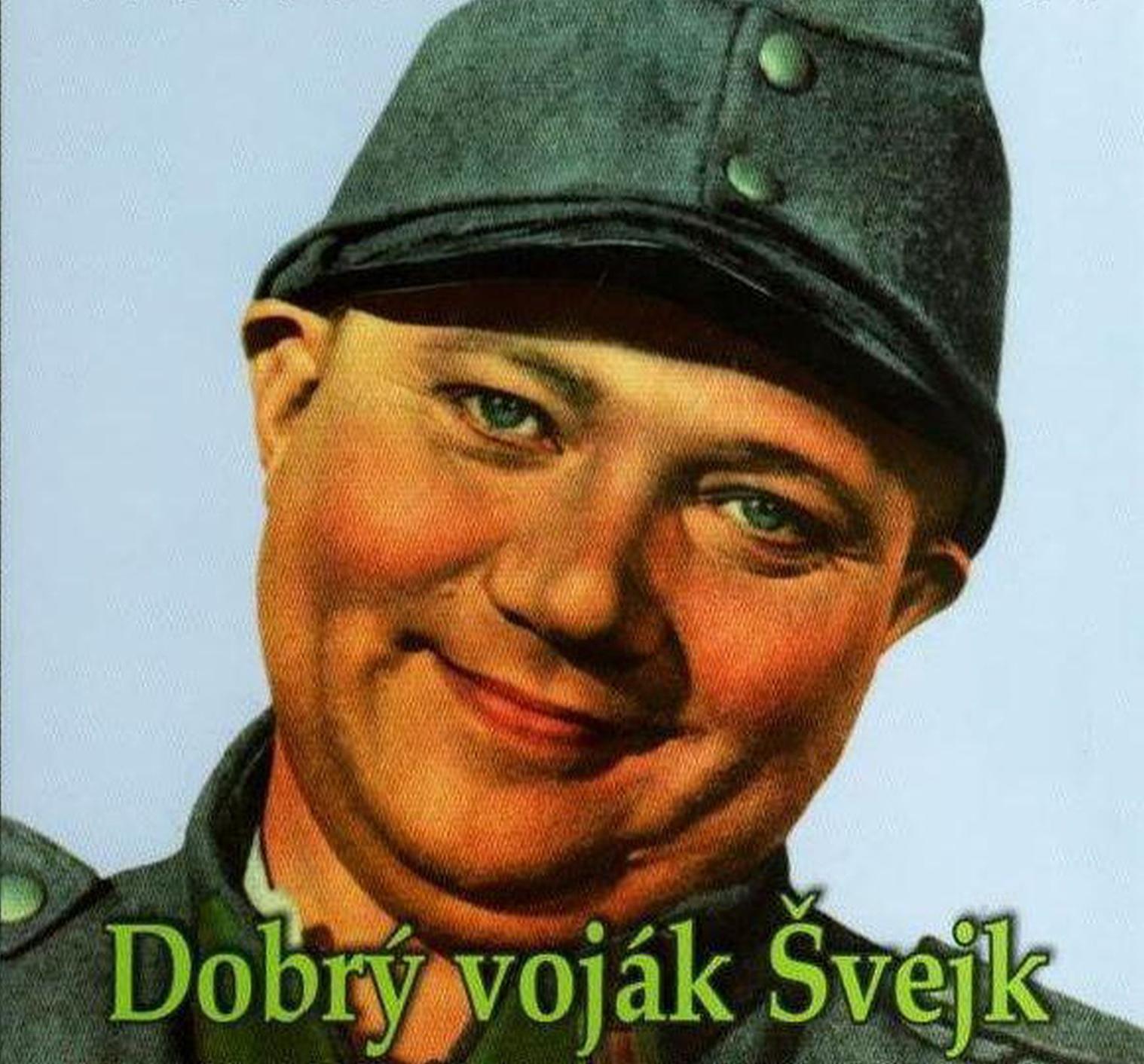

The 1956 film is still unforgettable thanks to the performance of the most beloved Czech actor of his generation: Rudolf Hrušínský

With the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War approaching, it is absolutely impossible not to mention the depictions of the Great War in Czech (or Czechoslovak) culture without making references to the legendary book by Jaroslav Hašek, as well as the immense influence it has obtained thanks to the numerous film, television and theatre adaptations.

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand begins what could be called the most famous and important novel of Czechoslovakian history: The Good Soldier Švejk (as transliterated in the English edition), a masterful condemnation of the absurdity of war, the protagonist of which, being a symbol of passive resistance, represents the national vision of “czechness” more than any other character. On the one hand there is the atonement, on the other an element of derision. The episodes of Švejk explore both sides. The Czechs often consider themselves to be victims of history, but at the same time love to make fun of it, precisely in the way Hašek does in his masterpiece. For the majority of Czechs, the most famous transposition of the film remains the immensely popular film Dobrý Voják Švejk (The Good Soldier Švejk: 1956) with the legendary actor Rudolf Hrušínský in the lead role. However, after decades of adaptations of Hašek’s satire (not just limited to the field of cinema), is this really the definitive version of the story?

Despite the fact that the soldier and dog seller appeared for the first time in 1912, the year of the publication of the book The Good Soldier Švejk and other strange stories (Dobrý voják Švejk a jiné podivné historky), the full work was published in four volumes from 1921 to 1923, the year in which the author passed away as a result of the tuberculosis he contracted during the war. The premature death of the writer, humorist and journalist from Prague (born in the Bohemian capital on April 30, 1883), interrupted the series, which however was completed by his friend and journalist Karel Vaněk. This did not prevent it from being an immediate success, despite taking time to obtain recognition by literary critics. In 1927 the German theatre director Edwin Piscator worked with the playwright Bertolt Brecht on Der Abenteuer des braven Soldaten Schwejk, an adaptation for the stage, described by the latter as “a montage from the novel”. The work aroused the enthusiasm of the Berlin audience and the rest of Central Europe until the repression by the Nazi dictatorship that limited the freedom of expression.

Despite the fact that the soldier and dog seller appeared for the first time in 1912, the year of the publication of the book The Good Soldier Švejk and other strange stories (Dobrý voják Švejk a jiné podivné historky), the full work was published in four volumes from 1921 to 1923, the year in which the author passed away as a result of the tuberculosis he contracted during the war. The premature death of the writer, humorist and journalist from Prague (born in the Bohemian capital on April 30, 1883), interrupted the series, which however was completed by his friend and journalist Karel Vaněk. This did not prevent it from being an immediate success, despite taking time to obtain recognition by literary critics. In 1927 the German theatre director Edwin Piscator worked with the playwright Bertolt Brecht on Der Abenteuer des braven Soldaten Schwejk, an adaptation for the stage, described by the latter as “a montage from the novel”. The work aroused the enthusiasm of the Berlin audience and the rest of Central Europe until the repression by the Nazi dictatorship that limited the freedom of expression.

Brecht himself remained so attached to the character, that in 1943, during his exile in the United States, he wrote the play Schweyk im Zweiten Weltkrieg (Švejk in World War II), in which the good soldier demolishes the authority of the Gestapo in a theatrical satire which was fierce and liberating in equal measure.

The first English translation appeared in 1930, while in its homeland, the tenth edition was published by 1936. Clearly Hašek was inspired by his experiences in the Austrian army in 1915, and at least initially, his intention was to make fun of the Austrian authorities. However, his defense of the little man standing against tyranny and oppression transcends the borders of his homeland. Švejk is considered to be a character representing the strength of the human spirit. If the literary criticism of the period was prejudiced against the improvised style of Hašek, the world of the cinema did not bear the same reservations. In 1926 the first film version appeared which used the author’s original dialogue in the form of inter-titles, directed by Karel Lamač, and featuring with Karel Noll as the actor in the role of Švejk. The film still today remains popular with the many fans of the writer, and especially among lovers of silent cinema. Three other versions in the period from 1926-1927, followed the adventures of Švejk.

The first sound version however, came in 1931. The film, directed by Martin Frič, who later became a very important director in Czechoslovak cinema, also boasted Saša Rašilov in the leading role in addition to the actor Hugo Haas before he reached fame as a Hollywood director and character actor in the 50s. The film has always been respected by lovers of Hašek, but, unfortunately only 57 minutes of footage have been preserved, so nowadays it is practically impossible to see the full version.

For those who seek an innovative creative interpretation of the adventures of Švejk, the three episodes of Osudy dobrého vojáka Švejka (“The Adventures of the Good Soldier Švejk”, 1954-55), from the king of animation Jiří Trnka, is quite simply unmissable. The work of the master from Plzeň, often dubbed “the Walt Disney of Eastern Europe”, is distinguished by filming puppetry using stop motion animation, while at the same time being able to capture the attention of the lovers of the book thanks to the use of original illustrations by Josef Lada, which appeared in the original novel. For the Czech public, the voice of legendary actor Jan Werich in the role of narrator also contributed to the success, while we must also recognise the skill of the director and his artistic choices. Firstly, Trnka understood that adapting the text of Hašek was a colossal task. He therefore decided to choose only the key episodes of the book, thus avoiding the narrative flaws of the writing of the author, considered a genius regarding character descriptions and dialogue, but not always with a convincing narrative style.

(A scene with Rudolf Hrušínský – Photo: Czech centre London)

The most famous film version, directed by Karel Steklý in 1956, divided a large part of the critics, some of whom consider it the best adaptation and the rest of which often think of it as the worst. Nevertheless, we must commend the director for the decision to divide his film into two parts: Dobrý voják Švejk from 1956 and Poslušně hlásím the following year. However, if the movie is successful, it is particularly thanks to the masterful interpretation of the most beloved Czechoslovak actor of his generation: Rudolf Hrušínský, who definitely gave us the best screen portrayal of the character, who however appears, perhaps misleadingly, as an idiot. The faithfulness to the original text proves to be both an advantage and a disadvantage. The work manages to retain the spirit of the writing of Hašek, but it loses a bit of the ambiguity that characterized the protagonist. Steklý emphasizes the stupidity of Švejk in the while failing to address the primary targets of the original author: bureaucracy and the effects on people.

Another page would be needed to talk about all the film versions of Švejk, produced in various countries such as the former Soviet Union, Poland, Romania, and even the United Kingdom. The German film Der brave Soldat Schwejk (1960), in particular, with the actor Heinz Rühmann, earned much success and was nominated for a Golden Globe award. One could also talk about the many never realized projects such as the version offered to Charlie Chaplin, which would have starred, the icon of film noir, Peter Lorre, an actor to whom Hrušínský was often compared. In the former Czechoslovakia however, it is evident that most of the war film products are pervaded with a certain “Švejkian” spirit, as well as questioning the morality of the war through comedy. Moreover, the nationalist discourse, predominant in war movies from other countries, remains in the background in their Czech counterparts with little emphasis on the combat scenes. Life and Extraordinary Adventures of Private Ivan Chonkin (Život to neobyčejná dobrodružství vojáka Ivana Čonkina), directed by Jiří Menzel in 1994 and based on the novel by the Russian Vladimir Vojnovich, is a sign that the spirit lives on. As in Švejk, the protagonists are not the heroes of the war movies of Hollywood, but ordinary people who demonstrate the absurdity of an authoritarian regime (in this case the Soviet totalitarian). It is precisely this spirit that shows the influence of Jaroslav Hašek’s masterpiece in Czech culture today.

by Lawrence Formisano