The prestigious, world-renowned Danish architecture firm won the international competition for the design of the new Vltavská Filharmonie

by Alessandro Canevari

Four simple moves: a partial vertical center cut from below followed by a small pull to separate the resulting flaps; a half-rotation along the vertical axis of symmetry; two more incisions of the volume from above along thirds; and a slight, but firm, pull of two opposing top vertices outward, et voilà, the skyscraper is served. Harder said than done, at least on paper. What appear to be four towers are actually, in the concept of the Danish studio Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), the result of the virtual manipulation of a single tower building which, thanks to cuts, separations and twists, maximizes the surface area and façade, opening up towards the surrounding environment, light and people. Both the conspicuous, and in some respects controversial, outcome and the disarming simplicity of the few simple gestures with which the Walter Tower (2007) was supposed to multiply the views of Prague’s skyline had attracted attention. An anonymous ninety-metre-high parallelepiped took on the iconic shape of a giant W in an instant. A strategy that had already been tried and tested with the design of the immense RÉN Building (2005) proposed for the Shanghai Expo in 2010, which had caused much discussion about the project and the new Danish studio.

It was the early 2000s and the newly-founded brand of the resourceful Bjarke Ingels was appearing on the international scene, gaining first-rate recognition and arousing, one might say deliberately, some controversy within a debate that by then had almost died down, but could still ignite at any moment, with faint and fleeting fervor, when appropriately stirred up. Ingels, then in his early thirties, had already mastered these dynamics with the flair of a profound connoisseur. The three-year experience at Rem Koolhaas’ studio had certainly not been spent in vain, the more malicious would say, forgetting to mention three other habits that Ingels seems to have learnt from the theorist of bigness: acceptance of modernity for what it is, juxtaposing apparently incongruous forms and uses with unsuspected nonchalance, attention to the design process and a prodigious editorial habit.

Fifteen years have passed since that much-discussed first prize remained on paper, a little too flashy and visionary, according to some, for the measured skylines of European capitals. Today BIG is a well-established global studio with a staff of more than six hundred. In addition to its headquarters in Copenhagen, it boasts four locations and several dozen projects spread over four continents which are not purely limited to architecture, but experiment across the board, dreaming of tomorrow’s world, without abandoning a certain complacency for challenge and provocation.

Today his return to the Czech capital is with all the honours of the victory of an international competition organised by the city administration and IPR Praha (Prague Institute of Planning and Development) for the prestigious design of the new Vltavská Filharmonie, the Vltava Philharmonic Hall for international audiences. A return fought against one hundred and twenty-five alternative proposals, of which nineteen finalists were submitted by the likes of SANAA, Ateliers Jean Nouvel, MVRDV, Diller Scofidio + Renfro and David Chipperfield Architects. BIG’s first place was followed by the five projects, in descending order of ranking, by Barozzi Veiga + Atelier M1, Bevk Perović Arhitekti, Petr Hájek Architekti and Snøhetta. A return that announces itself in grand style, but with the same immediate simplicity of its origins, today in more controlled forms suited to the institutional role, that makes BIG’s poetics a trump card, making its architectural gesture comprehensible, communicable and attractive to the general public.

The strong urban character of BIG’s proposal can be grasped at first glance. What is at stake here is much more than a concert hall complex, a school and a new home for the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra and the Prague Symphony Orchestra. It is the rebirth of a large central area of the city: the new Bubny-Zátory district, the western portion of Holešovice behind the north bank of the Vltava overlooking the island of Štvanice, right in front of River City Praha, the business centre built on the Karlín riverfront. Framed between the head of the Hlávka Bridge and a new square to the west and that of the Negrelli Viaduct and a new urban park to the east, the magic of BIG’s form thus transforms a key urban point that aspires to play the role of a hinge between the city’s contemporary cultural scene and the historical one.

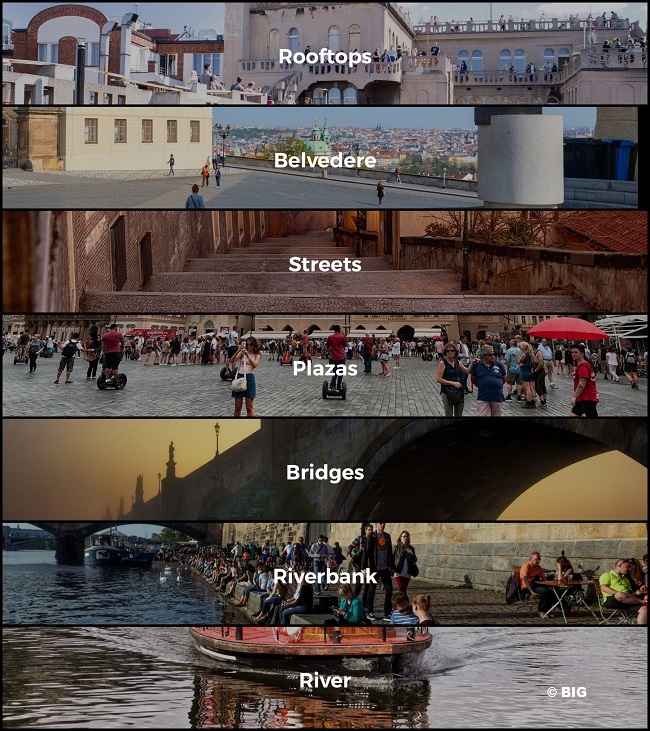

A conceptual section of unparalleled clarity summarizes the aim steering the entire project by stacking seven photographic strips of the Old Town. From the waters of the river, it goes up to the waterfront, then to the elevation of the historical bridges, to the squares of Staré Město and then on up the narrow steps of Malá Strana to the belvedere of the Castle, finally coming to a romantic halt at the panoramic rooftop elevation.

With the sincere simplicity of a gigantic urban scale origami, the architectural forms unfold like an accordion, tapering around the central volume of the Vltavská Filharmonie, making it an entirely walkable promenade that screwing up from the river to the rooftops. A gesture that is clearly reminiscent of the atelier, and even more so of the hotel that BIG recently built for the Audemars Piguet brand, but which displays the same public vocation as the ‘climbable façade’, with its even skiable slopes, of his famous CopenHill, the Amager waste-to-energy plant in Copenhagen, which Ingels himself proudly calls “a clear example of Hedonistic Sustainability”. Both immensely different and extraordinarily similar, these examples merge into a contradiction that in the oxymoronic BIG universe can only be seen as a quality or a source of pride. But, please, don’t call them practicable roofing. At Bubny-Zátory, the very city, lifting off from the river banks, rises to a vantage point. There, the giant equestrian statue of Jan Žižka soaring on the horizon from Žižkov Hill, and the rooftops of the old city shine southwest.

In the Prague nightscape, the new Filharmonie stands out like a huge paper lantern among the flickering city lights reflected in the slight ripples waters of the Vltava, as far as the eye can see among the hills. Inside the building, urban and social ambitions are in keeping with the accuracy, attention to detail, and the most advanced technical equipment to stage the great classical music for demanding Czech and international audiences. The concert halls, inscribed in the compactness of perfect squares, enclose a whirlwind of wood-clad galleries-shells from which the seats offer optimal views and acoustics – to instill in the audience a “greater sense of unity and shared experience”. Wooden essences typical of Šumava, the Bohemian Forest, clad the lower part of the terraces and extend into the foyer inspired by traditional local glasswork, paying homage to the Vltava’s long journey through the Bohemian territories.

The optimistic ‘pragmatic utopianism’ of BIG’s vision boldly, and sometimes with seemingly carefree recklessness, transforms the visionary aspirations of architects into successes for the general public. And the Vltavská Filharmonie seems to be no exception from its very beginnings. Complexities and contradictions of architecture, and ideally of the entire world, are overcome in the oxymoronic BIG universe with a light and charming prêt-à-porter confection with light-hearted religious observance of their motto. Yes, is more.