The Argentine revolutionary spent six months in Prague in 1966 without anyone noticing anything. Until one day Fidel Castro decided to make fun of the Czechoslovak services

Prague, April 1966. At Café Slavia, or Kavárna Slavia, the historical coffeehouse in front of the National Theatre, a man, one would imagine in his fifties, sits at a table. He looks at the Vltava flowing slowly out the window, drinking a coffee, he writes. Incipient baldness, with a slight hump, well-shaven, protruding teeth and square-rimmed glasses. It is not the first time he comes to Slavia. Concentrated, austere to the point of gloom, he could be a professor. The physique of an old soldier (a veteran?) is betrayed by coughing fits.

Who knows what he thinks of the artists and the leaders of the cultural revolution of the Sixties? Who knows what the artists and hippies who meet his eyes think of him? Nothing, probably, except that he is a foreigner, conservative in appearance, Uruguayan to those who dare to ask – but who is often accompanied by a young black man with very thick curly hair, who at least attracts the attention of the girls. It is not as if so many dark-skinned strangers are seen around here.

What does the Uruguayan write? Notes on “el hombre nuevo”, the new man. Indeed, nothing could be more banal for a Prague bar in 1966: a communist, like many others. No need to pay attention to it.

Cuba, 1971. Fidel Castro, Líder Máximo of Cuban communism, anticipating a surprise left to mature for five years, sends a note to the Czechoslovak interior ministry: he asks, if possible, to know the address of Che Guevara’s residence in Prague in the summer of 1966, in order to affix, if it were granted by the local authorities, a commemorative plaque. An unknown official, eight thousand kilometres to the East, opens his eyes like a cat in front of the headlights of a truck. What, excuse me? Che Guevara in Prague?

The Czechoslovak authorities prefer not to respond to the request of the Cubans, disguising the embarrassment with haughtiness. The StB, the dreaded secret services, had not noticed anything. To tell the truth, like the CIA and KGB: the Cubans had made the most famous revolutionary in the world disappear for months, in the middle of the cold war, allowing him to walk freely in one of the most beautiful capitals of Europe. Someone in Havana smoked a cigar, satisfied. Good jokes at the time of Che.

The secret year of Che

The secret year of Che

In the summer of 1965, after five years as minister of the Cuban government, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, the revolutionary par excellence, decided that office work was not suitable for him. He picked up the rifle again and returned to action following one of the secret missions of Castro’s services abroad, in the most delicate theatre of the 1960s: Africa. Amongst the turbulence of decolonization and the cold war, the guerrillas dreamed of exporting the revolution by supporting tiny Marxist vanguards in different countries. This is how Che found himself in the Congo at the end of 1965, in a catastrophic mission from which the Cubans hastily escaped after a few months. In December of that year, Fidel Castro announced at a party congress that Guevara would not return to Havana; the Argentine was at the service of the revolution, somewhere in the world, at the service of the oppressed peoples, a decision, it was said, more from Castro than from Che.

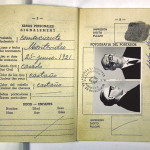

Unable to return home, waiting for his next destination, he arrived in Dar el Salaam, in the newly formed Tanzania. Here he was joined in February 1966 by Luis García Gutiérrez, known as Fisín, a Havana dentist, carrying a plane ticket and the tools of the trade. The plane ticket was for Prague. The tools of the trade, which trespassed the classical limits of dentistry by some length, served to make Che unrecognizable: a dental prosthesis, a hump, a crown of white hair on a false baldness. And for the most classic icing on the cake, square eyeglasses. This was Ramón Benítez, an Uruguayan, officially part of the escort of a communist official.

A revolutionary in Prague

The trick used by the Cubans was very simple. With Czechoslovakia being a country in socialist orbit, like the new Tanzania, the passage of people on this side of the iron curtain was relatively smooth. Castro’s diplomatic missions had already brought him to Prague, and Guevara himself had been greeted by President Antonín Novotný in 1961 and 1965, when the two countries had signed several cooperation agreements (it was the golden moment of relations between Cuba and Czechoslovakia, that froze after the Soviet invasion of ‘68). The Cubans consequently said they wanted to hide an agent in the Bohemian capital, with escort men, returning from the African mission. Ramón Benítez was a member of the escort. The StB did not suspected anything more than that, and they put up housing at the disposal of allied intelligence.

The first three months, between March and May 1966, Che spent them in a small apartment, at an address still unknown today, on Heřmanova street, in the residential district of Letná; between June and August in a villa in Ládví, the most peripheral neighborhood in the north-east of the city. At the end of the summer the new, and dramatically last mission of Che entered operational phase: Ramón Benítez took a flight to Cuba before leaving, once again in great secrecy, for Bolivia.

The protagonists speak

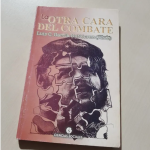

In recent years the history of Guevara /Benítez in Prague has come to light several times, thanks to the opening of the archives of the communist period. Various articles or journalistic works, including interviews with historians on national radio or gossip subsequently appearing in different magazines, with stories of bohemian lovers, drunkenness in local breweries and more generally 007-type fantasies originating from the little news from the StB notes. But to finally get more news, you have to start on the other side of the world. In 2014, the now 86-year-old Luis García Gutiérrez, the dentist Fisín, published the book “La otra cara del combate” (that is, The other side of the struggle) in Cuba, which recounts his memories as a “make-up artist” of the revolutionaries with Che, of course, on the cover. A couple of years later the book arrived in the hands of a young Cuban-Brazilian documentarist, Margarita Hernández, who decided to make a film of it. With little more than 50 years having passed since the events, the director decided to return to Cuba and meet several protagonists: fighters and officials who accompanied Che in the period of 1965-1966 in Congo, Tanzania and Prague. Thanks to their stories we have discovered curious anecdotes of the revolutionary in the golden city. We discover a Ramón Benítez who freely frequented Prague cafés, but fewer breweries; reckless in politics but conservative at home, little alcohol, no woman; lover of walks, annoyed by the climate (his asthma made a reappearance). Ulises Lascaille, his aide, at the time aged twenty, remembers when he brought a Beatles record and ended up on the receiving end of bad words from Guevara, who preferred Latin American classics. After a few days, however, the revolutionary softened and occasionally let himself go to an “Ulises, put on a little of that capitalist music that I like…”. Ulises, now a retired journalist in Havana, was dismissed shortly after – his skin colour and his thick curly hair apparently attracted too much attention, especially of the local women. Thus, in the move to the house in Ládví, Guevara was joined by Fisín himself, still with his tools of the trade, ready to “make him even older” before leaving…

The film “Che, memorias de un año secreto” (Che, memories of a secret year), released in 2018, was presented in Prague at the Spanish language film festival La Película, in February 2019. Scheduled at Kino Světozor, it was sold out so quickly that the organizers added a second screening, which also turned out to be sold-out.

Political ideology aside, the icon Che Guevara is a huge symbol of the 20th century, and the spy story on the streets of the capital is highly captivating. Like that unknown official who read Fidel Castro’s message, the audience at the cinema must have been stunned: “Che Guevara in Prague?”

by Giuseppe Picheca