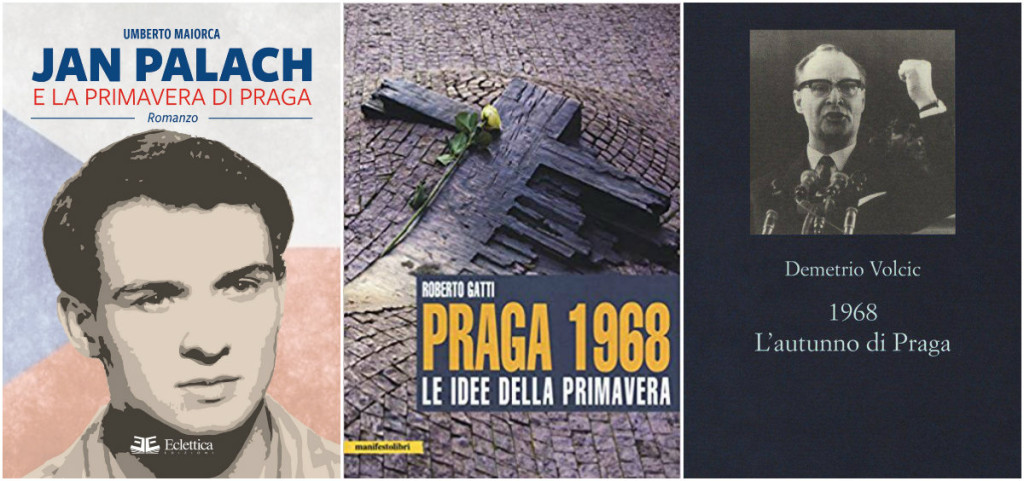

Jan Palach e la Primavera di Praga

The book by Umberto Maiorca is being released, about Jan Palach, the young Czechoslovakian who on January 19, 1969, five months after the Warsaw Pact tanks entered the Bohemian capital, decided to set himself on fire in Wenceslas Square in protest against the foreign occupation and cry out to the world the desire for freedom of his people. With his gesture, Jan Palach became a hero and a symbol of freedom for a generation of students and militants. His gesture was not suicide, but an act driven by the desire to awaken the conscience of fellow citizens who after experiencing an exhilarating period of freedom during the Prague Spring, were forced to confront the “normalization” imposed by the Soviets. The young Czechoslovak student was living with impatience on his skin the deprivation of freedom and humanity imposed by Soviet communism. Jan loved his homeland and wanted to contribute with an extreme gesture, a martyr, to the liberation of his people from an unjust and insulting oppression.

Umberto Maiorca,

Jan Palach e la Primavera di Praga,

Publisher: Eclettica (2019),

128 p.

Praga 1968. Le idee della Primavera

Roberto Gatti in his book “Prague 1968. The ideas of Spring”, retraces a long piece of history since now relegated to oblivion and eclipsed in the historical memory of much of the left, while trying to rediscover important elements that can answer the many questions. Is there a theoretically relevant and still topical significance of the Czechoslovakian political experience of 1968, which became known as the “Prague Spring?” And what is the relationship between this experience and the 1968 that developed beyond the Berlin Wall that divided Western countries from the Soviet bloc? The Prague Spring was the final episode of an attempt to build the hegemony of an idea of a different and more humane socialism than the techno-bureaucratic one that emerged in the post-WWII years. The goal was a general rise in living standards, combined with the development of freedom and democratic participation.

Roberto Gatti,

Praga 1968. Le idee della Primavera,

Publisher: Manifestolibri (2018),

111 p.

1968. L’autunno di Praga

Demetrio Volcic, for many decades a RAI correspondent from the Eastern European communist countries, directly recounts what happened in the days of the repression of the Prague Spring by the invasion of the Warsaw Pact tanks. From his chronicle, enlivened by being born as a narrative in a live voice for the radio later transcribed in the book, the way in which the author presents the facts is particularly striking. It is the concrete spatial point of view, that he assumes that gives him the power to drag the reader in the middle of the scene, as if he were there side by side with those boys who watched, astonished and desperate, the other boys of the “brother army coming to free them”. Or in front of Jan Palach, who soaked his body with petrol. Or at the supermarket with a simple and smiling Dubček. Or sitting in front of Brezhnev slightly tipsy, unable to believe that a head of the regime possesses so much abstract idealism. This book is a vivid historical testimony. It is also an example of the harmonious naturalness of representation that knows how to reach the art of the reporter.

Demetrio Volcic,

1968. L’autunno di Praga,

Editore: Sellerio (2018),

192 p.