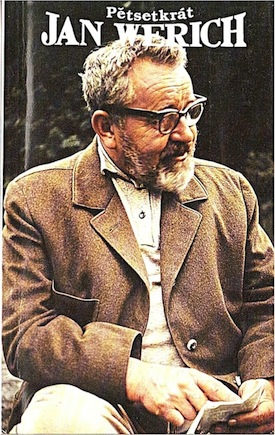

Deep voice, rosy cheeks and an appearance like Santa Claus. Over thirty years from his death, the immensely popular Czech actor continues to influence Czech culture

From the 1930s, actor, playwright and screenwriter Jan Werich enchanted the Czechoslovakian nation with his film and theatre productions, often written with his friend and partner Jiří Voskovec, and addressing brave, and risky political issues for the time. To understand just how important he is in his homeland, it is enough to mention that in the program Největší Čech (the greatest Czech), on air in 2005, in which viewers voted for the most important figures of their nation, Werich finished in sixth place, ahead of the illustrious names of Jan Hus, Antonín Dvořák and Karel Čapek. It would be difficult to find another country in which an actor or playwright has had such importance. Abroad he will be remembered as the actor who was supposed to play the most popular villain and main nemesis of James Bond, Ernst Blofeld. However, what made him so popular?

Born in Prague in 1905, the young Werich grew up in the neighborhood of Dejvice. The meeting which marked his destiny took place in school (on Křemencova street), where he made friends with Jiří Voskovec. It was the beginning of an extraordinary artistic partnership, which after a brief stint in the editorial staff of the magazine Přerod, really took off with their participation in Osvobozené Theatre (“The Liberated theatre”) in Prague, linked to the avant-garde group Devětsil.

Vest pocket revue of the year 1927, was their first notable work, inspired by the French avant-garde, in which they recreated an absurd, fantasy world, while in terms of acting, they were influenced by Charlie Chaplin, Stan Laurel, Oliver Hardy and Maurice Chevalier, with many elements taken from thecircus world (such as the use of masks). However, in 1932 they began to mix their typical comedy, clownish yet refined, with more political themes. The productions, clearly left oriented, were typically satires, commentaries on unemployment and social problems, critical of politicians and dictators.

The key work in this stage of their career was Caesar, in which they interpreted Benito Mussolini as a Caesar eager for war. The comedy is a warning about the dangers of the fascism brewing in Europe at the time (but the Czechoslovakian president Edvard Beneš however, considered the play anti-democratic). The following year, however, the two managed to create a stronger stir with Osel a Stín (The ass and the shadow), the anti-Nazi tone of which infuriated the German embassy in Prague. Kat a blázen (The executioner and the fool), another anti-fascist work, was the final straw: the German Embassy did not accept the criticism of Adolf Hitler. Werich and Voskovec were consequently expelled from the U Nováků Theatre.

It was also at this time, when the duo wrote and starred in a series of left wing leaning films, directed by a very important Czechoslovakian director in the era, Martin Frič. The Munich agreement in September 1938, however, marked the end of “The Liberated Theatre”, and the two actors were forced to emigrate to the United States. Exile however, did not slow their activity down. They spent the Second World War in America where they staged plays in English for the American public, and in Czech for the Czechoslovakian community. In addition, they broadcast anti-Nazi programs on the radio for Voice of America, the official service of the U.S. Government. After the war, for the first time, the paths of the two masters of Czech cinema and theatre divided. Werich returned to his liberated country in 1945, as did Voskovec a year later, but attempts to redo “The Liberated Theatre”, were in vain. In the new political climate, satire was no longer accepted. Voskovec decided to leave his homeland for good, and remained in the United States until his death in 1981. The Bohemian actor, known in America as George Voskovec, became a highly respected supporting actor in films from the 50s onwards, with roles in classics like 12 Angry Men and The Spy Who Came in from the cold, but naturally could not reach the level of fame he had in his homeland. The fate of Werich, however, was quite different.

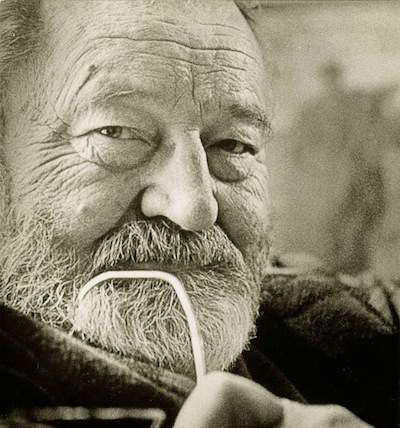

The great bearded actor, considered to be similar in appearance to Ernest Hemingway, managed to find a new theatrical collaborator in Miroslav Horníček, but it was in films where he really made his mark. Císařův Pekař – Pekařův Císař (The Emperor and the Golem: 1951), in which he played the dual role of Emperor Rudolph II and a baker, is one of his best known hits. The film, directed by Martin Frič, is still a rare example of a work which was appreciated by the public as much as it was by the communist government, who approved songs such as “We want to work (and not live!) in peace”, and lines like “He can do this and she can do that, when we share, everyone will have everything”, Communist overtones initially discouraged the actor from accepting the role, but, in the end, the film gained a certain degree of success abroad (especially in the U.S.), where it was released in a cut version, without the communist propaganda. Also in the same decade, Byl jednou jeden Král (Once Upon a Time, There Was a King, 1955), a fairytale with the Czechoslovak King of comedy Vlasta Burian, and especially Až přijde kocour, (The Cassandra Cat: 1963), another fairy tale for adults, and winner of the special Jury Prize at the 16th Cannes Film Festival.

Despite his political activism, Werich by now understood that to work, he had to accept censorship and the propaganda of Communist cinema. Being already the most beloved actor of Czechoslovakia, in 1967, he got an offer to participate in a film that could have made him famous all over the world, the James Bond classic – You Only Live Twice, in which he was to play the villain Ernst Stavro Blofeld, who would become the most popular of the series. After about a week the Prague-born actor, however, was replaced by actor Donald Pleasance, with the official excuse that Werich was very sick. To this day, the real reason remains a mystery. Some sources indicate that producer Albert Broccoli wasn’t convinced with his initial choice, finding too much similarity between the Bohemian and Santa Claus, who he deemed to be unsuited to the role of the villain planning world domination. There is however a second theory, a more likely one: that the regime threatened not allowing him to work in his homeland again if he finished the film.

The opportunity to become an international star had gone, but the actor was now willing to water down his political activism in order to work in his country. In ’68 he signed the manifesto Dva tisíce slov (Two thousand words) with the reforms proposed by Ludvík Vaculík after the election of Alexander Dubček. After the Russian invasion , Werich headed to Vienna (where he met his friend Voskovec), but quickly realized that he could not live without acting, and his homeland, where he returned after a year. His subsequent actions, however, disappointed dissidents in his country. He not only didn’t sign Charter 77, the famous document (partly created by Václav Havel) in defense of human and civil rights, but did sign the anti-Charter 77, although he later claimed to have been deceived. Nevertheless, the events did not negatively affect his popularity, and he remains a much remembered personality for the Czechs for his expressive roles during the communist era, and for his new definitions of the Czechoslovak theatre of the absurd. Since his death in 1980, thousands of fans continue to visit his baroque villa on the island of Kampa, and his tomb at Olšanské cemetery, where he rests next to the tomb of his friend Voskovec.

by Lawrence Formisano