The extraordinary story of the Slovenian Jože Plečnik, with whom Tomáš G. Masaryk entrusted the architectural renaissance of the Prague Castle in 1920

Once upon a time in a not too distant past, in the heart of Europe, there was a majestic castle overlooking a city with golden roofs. The large castle stood on a hill, along a placid river. After a long period of neglect, the castle became the residence of a learned and wise ruler who cared about the identity of his people and nation, which had become independent after centuries of foreign rule. Alongside this benevolent ruler, loved by his people, lived his highly cultured daughter named Alice.

In this city of golden roofs, there was a foreign architect who had lived there for almost ten years, having been exiled from his native country by necessity, and due to his origins also from the country in which he made his fortune. A peculiar type of very few words, but of great talent and skill that far from home, for which he had always felt a great longing, he had achieved a certain fame through hard work. Despite some moments of hardship, the city with golden roofs was offering a period of serenity to the taciturn architect who here was dedicating himself with extraordinary passion for teaching, earning the admiration of students and many colleagues.

Having moved with some hesitation, and with his thoughts always turned towards his native land, he did not expect at all that this magical city would allow him to realize many of his youthful dreams, giving him great satisfaction. Once he received a good offer at home after twenty years of absence, the shy gentleman with a stern look, was about to leave the city with golden roofs and return home when the imponderable occurred. It was almost as a sign of gratitude, even though he was a foreigner, that the industrious city entrusted their beloved castle to his care. The meeting with the wise ruler and his daughter Alice did the rest, by offering him the unexpected opportunity to send his name into history. The diffident, hieratic looking architect found the interlocutors to be something he had never expected. Among the three, a deep intellectual understanding was born that transformed the view as in a solo piece dedicated to the art and identity of the people, materializing in the objective to turn the largest castle into the national symbol of freedom, independence and democracy.

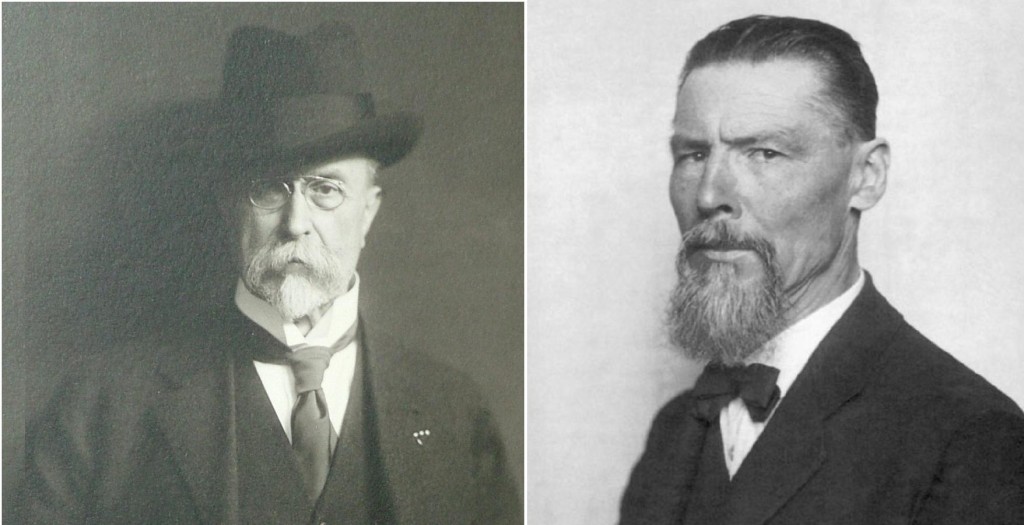

Putting aside the fairy tale aspect and looking at history, it is not difficult to assign a name and age to these characters and scenarios. Of course, the more astute readers here will have already made the necessary character exchanges themselves. The extraordinary early twentieth century story of the fruitful meeting between President Tomáš G. Masaryk, his daughter Alice and the Slovenian architect Jože Plečnik possesses all the credentials to be told like a fairy tale. Nothing is missing: the stunning setting, exceptional characters, not to mention the twists. However, far from wanting this postmodern game to get out of hand, one must pick up again from the facts, while quickly retracing the stages of this curious story.

Putting aside the fairy tale aspect and looking at history, it is not difficult to assign a name and age to these characters and scenarios. Of course, the more astute readers here will have already made the necessary character exchanges themselves. The extraordinary early twentieth century story of the fruitful meeting between President Tomáš G. Masaryk, his daughter Alice and the Slovenian architect Jože Plečnik possesses all the credentials to be told like a fairy tale. Nothing is missing: the stunning setting, exceptional characters, not to mention the twists. However, far from wanting this postmodern game to get out of hand, one must pick up again from the facts, while quickly retracing the stages of this curious story.

Of humble origins, the talented and shy Jože Plečnik left Ljubljana late twenties to Vienna, entering almost immediately in the studio of the great Otto Wagner, with whom he worked for a decade earning a notable degree of fame.

Among the many teachings from the master, he was struck by the idea that the architect had to regain what had been taken away from the power of engineers. Hence his consideration of even the smallest constituent of the human environment worthy of the love and attention of the architect, outlining a figure of multiform talent. This was the guiding light that led him through his entire career and enabled the young Plečnik to become among the pioneers of the new approach to industrial design.

The growing aversion of the Slavs, but especially the harsh criticism leveled at his project for the Heiliggeistkirche in Vienna led him to leave the city, albeit reluctantly, in 1911.

Although his fame had preceded him in Prague, he had deep misgivings about moving following the call from his friend Jan Kotěra at the Škola pro dekorativní architekturu, being frightened both by his poor knowledge of the language and the conviction of not being a good teacher. Plečnik arrived in Prague hesitant, but having expected him to rethink it over, Kotěra “trapped” him by having already procured a tailcoat and a meeting with the minister of education. Plečnik undertook his teaching career in Prague by applying himself with meticulous dedication, as was evident from the correspondence with students, but without receiving any commission for a decade.

The year 1920 was a turbulent year for Plečnik, because he was afraid of heading towards his “artistic death” for having accepted an appointment as professor at the Polytechnical University of Ljubljana. However, in November that year, after several rejections, he was appointed architect of the Castle by President Masaryk.

From Plečnik biographies, a character emerges of a man led to isolation, only ready to welcome you as a customer if you were able to display full confidence in him. Chosen almost due to elective affinity, they were rewarded by having his talent and knowledge at their disposal, which he was ready to apply to the project with devout passion. This happened in its most perfect form on the understanding he had with President Masaryk and Alice, based on shared ideals and intentions.

The Habsburgs had left the castle in a situation of abandonment, and the task of bringing it back to the luster worthy of a national monument presented Plečnik with an enormous amount of work which included the most diverse subjects: from the interior to the gardens, from the restoration project of new monuments, to the arrangement of the archaeological excavations. Many anecdotes have been told about the creation of these works, each of which for Plečnik was like the single brush stroke of a large fresco, but also cause for concern.

Without scratching the strength of the tradition that the entire complex contains in itself, Hradčany was progressively shaped by Plečnik with skilful personal and recognizable “touches”, without ever sticking to a precise program or theory.

Often we read that through the work on the castle Plečnik intended to lay the foundations for a new style, but in his eyes and in those of Alice and Tomáš Masaryk, the castle was simultaneously acquiring the value of a first step towards a Pan-Slavic artistic expression – thus to the centre of a clear political perspective.

Thanks to Alice’s advice and the President who defended him from public attacks, Plečnik worked in minute detail. The juxtaposition of new elements with pre-existing structures had the specific intent to give the unit the monumentality that was supposed to tighten a common thread between the ideals of the new democratic state, and the ancient Greek democracy.

The foresight of Masaryk had pushed Plečnik to develop an impressive city plan which would link the castle to the northern part of the city, but public opinion strongly criticized the proposal. Plečnik, feeling under attack, decided to leave Prague despite the elder Masaryk’s efforts to keep him; it was 1934.

A year later, the now eighty-year-old Masaryk resigned. Genuinely shocked by this choice and deprived of the security of his “patron” Plečnik abandoned his role, leaving the magnificent Hradčany in the hands of Pavel Janák.

by Alessandro Canevari