The life of the painter is intertwined with one of the most fascinating place in the Czech Republic, Český Krumlov

The small Renaissance-style jewel of Český Krumlov, in Southern Bohemia was a great source of inspiration for the Austrian painter Egon Schiele, not only because his mother, Maria Soukup, was born there, but also because in this place the youthful feelings and enchanted landscapes found perfect harmony in the stylistic evolution of the so-called pornographer of Vienna.

Developed over the centuries under the care of the Habsburg princes and the Jesuits, Český Krumlov is nowadays above all a touristic destination, although recently deserted, or almost so, due to the Coronavirus pandemic. We visited it during a beautiful autumn day, with the sun shining on the enchanting rooftops and reflecting in the Moldau, the river sinuously crossing the village. Young Schiele, born in 1890, visited beautiful Krumau as a child, a place where the majority of the inhabitants were German-speaking back then. He spent here his summers from one century to the next; the Budějovice Arch, which leads to the historic center, was the first monument in Krumlov that he painted, in 1906.

After graduating the Akademie der bildenden Künste in Vienna, Schiele started up as a freelance author, as we could define him today. Not even in his twenties, in the summer of 1909, he inaugurated an exhibition along with friends and colleagues of the “Neukunstgruppe”: Franz Wiegele, Albert Paris von Gütersloh, Anton Faistauer and Anton Peschka. It’s to the latter that Schiele admits during spring of the following year that he was tired of the decadent Austrian capital: since he attracted the envy of citizens and colleagues, he intended to leave. “I want to move to the Bohemian Forest”, he wrote. No sooner said than done: in May 1910, Schiele settled in Krumlov, on Masná 133, in the house of Thomas Oggolter.

After graduating the Akademie der bildenden Künste in Vienna, Schiele started up as a freelance author, as we could define him today. Not even in his twenties, in the summer of 1909, he inaugurated an exhibition along with friends and colleagues of the “Neukunstgruppe”: Franz Wiegele, Albert Paris von Gütersloh, Anton Faistauer and Anton Peschka. It’s to the latter that Schiele admits during spring of the following year that he was tired of the decadent Austrian capital: since he attracted the envy of citizens and colleagues, he intended to leave. “I want to move to the Bohemian Forest”, he wrote. No sooner said than done: in May 1910, Schiele settled in Krumlov, on Masná 133, in the house of Thomas Oggolter.

Peschka (who later married Gerti Schiele, Egon’s sister in Krumau) and his friend Erwin Osen joined him shortly after: the three of them immediately made themselves noticed in the village, where they inevitably attracted people’s curiosity, and then the indignation of the local population.

Among them three, Schiele was the one in love with Krumau. It is here that he perfected his style and reached his expressive maturity on canvas. Attracted more and more by Expressionism and Art Nouveau, which he helped create, Schiele illustrated varied items in Krumlov, including the graceful wooden and stone houses on the river.

Being broke, in winter 1910, he returned to Vienna trying to collect some money from his customers in the Austrian capital. Among these, the architects Josef Hoffman, Otto Wagner and Otto Prutscher, the art historians Heinrich Benesch and Arthur Roessler. Precisely the latter one was his greatest benefactor and admirer.

In the spring of 1911, he was back in Krumlov, where his local protégé and admirer Willi Lidl had found him a new home, including his studio in the South of the city in Linecká (a few minutes walk from the center), owned by a certain Max Tschunko. Recognizing the talent of the young Viennese, he made the studio available to him free of charge. Later on, Lidl would have had problems in the highly provincial Krumlov, for the help given to Schiele and for his deep sentimental bond with the painter, to the point that he was even expelled from school. While the beloved Egon was absent, Willi wrote him short letters (“Dear Schiele!”) where he reported on the administrative matters that he impeccably attended for him in the village.

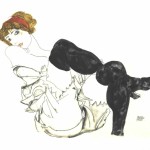

The big news of Schiele’s return in Krumau was that he brought his fiancée Wally Neuzil with him, his muse and former model of his friend and mentor, Gustav Klimt. The author of “The Kiss” discovered and appreciated Schiele in 1907 and helped him integrate in the Viennese artistic establishment. In Krumlov, Wally and Egon didn’t have an easy life: the sketches depicting his young lover in deliberately erotic poses toured the village, which unanimously condemned them. Furthermore, Schiele’s letter of protest addressed to the school in defense of Lidl caused shock in Krumau. The painter’s reputation was further deteriorated with a raise of the suspicions of relations with minors, who were invited in his studio to be portrayed. Soon, parents and teachers forbid their little children from following the damned Viennese on the “road to perdition”.

Scandal after scandal, it took just a few months for the inhabitants of Krumlov to force Schiele and the beautiful Neuzil to leave the village. Even though reluctant, and pressured by the people, Tschunko also had to issue an eviction order for his tenant. On the day of his farewell, Schiele wrote down in his diary that people didn’t know what they were doing by asking him to go away. On the other hand, the inhabitants felt relieved: the monster was leaving; and even when he returned later on for occasional visits, he continued to be frowned upon.

Despite all his love for Krumlov, this place was very unwelcoming to the exuberant and creative Egon Schiele: the country-style reality – conservative, gossipy and puritan – was completely incompatible with his eccentricity, which rose perplexity even in multicultural Vienna.

Portraying naked people was not only breaking apart from the aesthetic and artistic traditions of the time (it was also the era of Sigmund Freud’s discoveries) but was considered indecent. On the other hand, we must acknowledge that the pétite bourgeoisie of South Bohemia never wanted to integrate the artist in its community, not even after the cheerful evenings and meetings at Café Fink, which no longer exists, where – regardless of debts – the young Schiele sometimes offered everyone a drink.

Either way, Český Krumlov shaped young Egon: it helped him resist the cruel attacks of people and refine his unmistakable style. Even though the village had architecturally important Gothic and Renaissance elements, which are still well preserved today, Schiele only rarely painted them in his works. He preferred to devote himself to the banality of everyday life, to the expressiveness of the shapes, emotions and miseries of the human being.

On the other hand, in Krumlov there was no lack of sources of inspiration: although the village is delightful in spring and summer, in the second half of autumn and winter it must be rather austere. Therefore, during his stay in South Bohemia, the artist focused precisely on themes such as coldness, desolation, mortality, depression and human imperfection. Critics agree that there is something gloomy in Krumau’s paintings: Schiele was obsessed with his mother’s village and loved to be captivated and inspired by the great Dlouhá street, which inspired his “Dead City” of 1910, by the Křížová hora, the surrounding mountains and the Swiss-style houses. And more so by skies, sunsets, and imagined autumns.

Schiele became Schiele also by representing the magic of his beloved Krumlov, where he explored tonal variations, the raw and rough shape, as well as breaking apart from the beauty canons of the early twentieth century. The Schielian creation was so intense due to his need to cover debts, but he was sincerely in love with the town: he adored its flowers, hills, rocks, air, wind and water. Therefore, Krumlov inspired the title of many of Schiele’s works. He painted one of his last creations on his last trip in September 1917 with his wife Edith Harms, more socially acceptable than beautiful Wally, from whom he separated in 1915.

As for Český Krumlov, as we know it today, it could be renamed “Schielestadt”. Here, everything reminds us of Schiele: from the studio-atelier in Linecká 342 to the house of his mother Maria, in Parkán 111; from the artist’s home in Masná 133 to the art center bearing his name in Široká 71, which gathers his creations, as well as – celebrating the 130th anniversary of his birth – the sparkling canvases of Alena Anderlová, the faded ones of Judith Zillich, the abstract art of Tets Ohnari. On the top floor of the gallery, in a dark attic with white columns, we find the Schielian world, among mannequins and photos, sketches, funeral masks, easels, the artist’s letters and postcards, collections of drawings between painting and pencil art, and projections of paintings depicting Krumau.

Through black and white photos of Krumlov, the photographer Josef Seidel (exhibited as well in the Egon Schiele Art Centrum) shows to the public the city where the artist scandalized with his obsessions and quirks; between raw nudity, corruption of the body and restless and violent expressiveness. Seidel’s photos depict a village immovable in time, almost stuck in a black and white lockdown: a small and magical Bohemian village that the young artist loved like a mother.

by Amedeo Gasparini