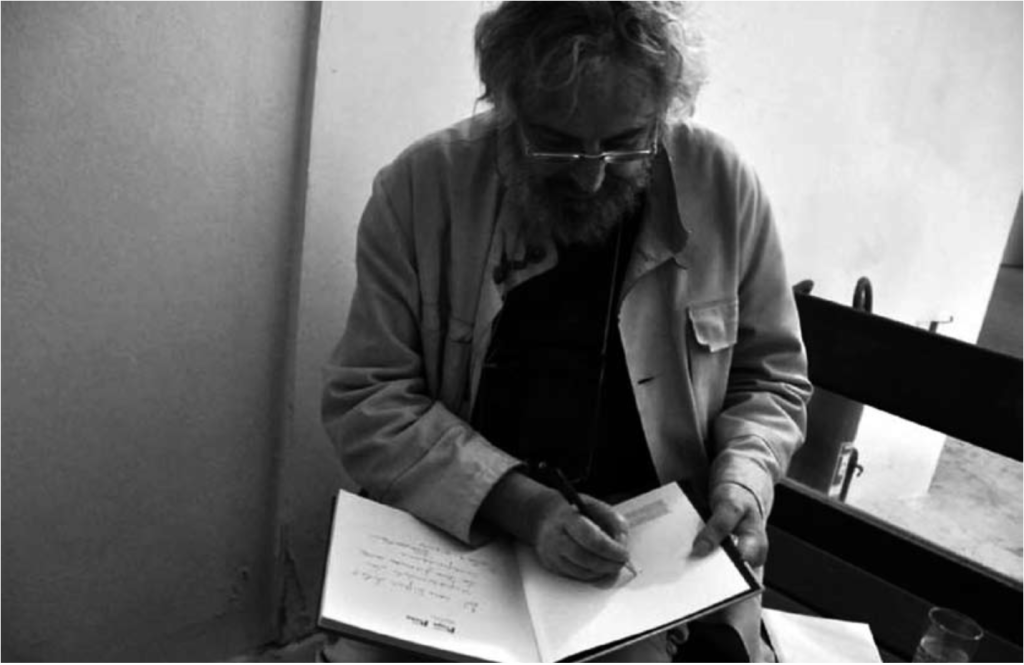

Interview with Sergio Corduas, considered the greatest bohemistics expert in Italy, translator and teacher of Czech Language and Literature at the Ca’ University, Foscari in Venezia

Professor, how did this passion for the Czech language and culture begin?

It all started because I had read a book, on which later I did my thesis, that made me fall in love with this language,despite the fact that I had enrolled for Russian because, since I was a child, at14 I had read Dostoevskij and Gogol’. Then I discovered that at university a second Slav language had become obligatory and that the professor of Russian literature, Angelo Maria Ripellino who fascinated all of us, was also teaching Czech language and literature, therefore, I chose as a second compulsory language the Czech language, because Ripellino was there.

Not only for the language itself, then?

No, not yet. Then, however, I got a fateful summer scholarship in Prague and I definitely fell in love with the city – I am referring to 1964, which is centuries ago – and I also fell in love with its language and a book which I had read in the meantime, Švejk, on which I decided to do my thesis. On my return to Rome I went to Ripellino and told him that I wanted to invert things and do the Czech language as the main language and, his answer was: “Dear Sergio, you can’t! But that means that we will send you on a scholarship to Prague. This is what we did and I, from the second year on, was on a scholarship always in the city of Prague. I remember that to do my degree thesis, the original ones of the past years, on an argument of Czech literature, you needed special permission from the faculty president.

The Czech language, though, is considered by many Italians resident in Prague as a stumbling block. Is it really so difficult?

No, it is not at all true that it is difficult. It is those who say so who do not have the right care to learn it and are not committed. I am sorry, they are totally wrong.

What advice would you give to make it more enjoyable and easier to learn?

You have to stimulate the mind of people and that is not easy and, therefore, it is just plain prejudice. The truth is that if an Italiian studies the Czech language and if he has a minimum amount of general linguistic talent, he will learn it very well, much better than the French or the English.

The Italians and Czech literature: what has changed in the last 20 years, I mean, after the fall of the wall and the Velvet revolution? Are Czech writers read more now? And if so, why?

Czech authors are read more than in the past because more translations are available compared to 20 years ago; the problem is, however, who does the translating work, how it is done, and also to a great extent, for which publisher. If a small publisher translates a Czech author who is not first rate, he does, anyway, a good thing but then, that book will not be read by many, will not be successful on the market and will not receive reviews.

Which, according to you, is the author who has not yet been translated, that would be worth translating, or that you would like to translate?

Karolina Světlá, if we speak about the nineteenth century – however, no publisher would accept. But I would rather speak about the fact that there are a few great names of Czech literature that have been translated into Italian, but are impossible to find, such as Karel Hynek Mácha’s epic poem, May. Who would be able to find May by Mácha, translated by Ettore Lo Gatto in the fifties?

Then, why don’t you propose it to a publisher, in view of the fact that you are an authority on the subject?

I have done so, but the answer is always the same. Poetry does not sell.

And then, I am particularly demanding. If we have to do May again, as should be the case, it must be done in this way: Czech parallel text but, at this point, the publisher would hedge, then free and rhyming verse translation. And which publisher would be willing to do that? A publishing house founded by some of my ex-students, la Poldi Libri, has translated in the last few years, four great Czech writers, which the Italians didn’t know, and which even the Czechs tend to neglect because they are rather elite writers. For example: Jakub Deml, Richard Weiner and Josef Čapek. Another writer who should be re-translated is Němcová, Babička is impossible to find.

Professor, let’s change the subject. You said you had arrived here the first time in 1964, so a number of things have changed since then… Allow me to ask you, even if the question is somewhat rhetoric, but how has Prague changed and what do you miss of that period?

Of that period I perhaps miss the solidarity that was present among people due to the positive consequence of dictatorships, of powerful regimes. They have this peculiar advantage: they make the people they oppress become more united and solidary towards each other.This solidarity is still present here and there, but it is being lost due to our “egoism-consumerism” … there is also the problem of the so called globalization, therefore, it is no longer the Prague of the past, that is for sure. One thing, however, which must be taken into account is that there isn’t only Prague. If you go to Brno, as I presume you have, you will discover that there are still human towns. Prague has always been neurotic, even before the fall of the wall, but at the time, however, it was “too human”, just to quote someone. An now, it is … too .. I was about to use a swear word one should not say … it is too disgraceful! Too “vypucovaná” as you say in the Czech language.

The presence of out or in bouncers is not worthy of Prague.

What are today, then, the positive aspects of the city?

What I am comforted by is the attitude of most university youths which is still based on an interest for things. They are still verist youngsters. It is true, however, that they do not know anything by now about 1989 or about 1968. This is their parents’ fault and it is not only a Czech phenomenon; also in our country, what do we know about fascism, for example?

Coming back to our own garden, what is the present Bohemian situation in Italy?

Well, if we intend a whole number of people scattered around a number of universitites to study Czech aspects, in a somewhat organized, coherent way, with a comprehensive line, well in this sense, an Italian Bohemian situation does not exist! If for Bohemian we intend the editorial policy of publishing companies, then, things are much better for the reasons that we stated before. Much more is published, but I would make a little remark, which is the following: when one publishes a book which is not strictly necessary to the Italian context, it takes away space from another book which is probably strictly necessary to that context, and that, however, will not find space.