In memory of Natalya Gorbanevskaya, Russian poet and dissident who died last November. In August 1968, she challenged the Kremlin in defense of occupied Czechoslovakia

The story of Gorbanevskaya shows that relations between Prague and Moscow are far more complex than stories about the Cold War, or the current economic news on Russian properties in Bohemian villages

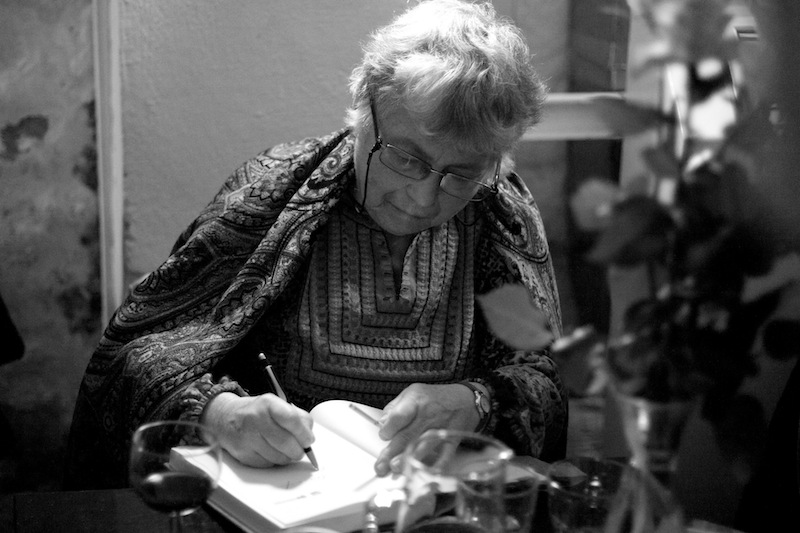

(Natalya Gorbanevskaya at the literary café Fra, 28 October 2012 – Photo: Ondřej Lipár)

It is August 25, 1968, a Sunday morning. The summer, in Moscow, is in arrival. The Communist Party displays tranquility, but in the heart of the Soviet capital a new political tension is seeping in. Muscovites still have the editorial of Pravda from Thursday the 22nd under their eyes, entitled “The defense of socialism is the highest international duty”; an article with which the Party newspaper justifies the military invasion of Czechoslovakia, completed a few hours earlier. In Red Square, in front of the astonishing array of colours, towers and onion domes that is the Cathedral of Saint Basil, Lobnoye Mesto is empty. It is the name (“the place of skulls!”) of a platform of white stone, forty feet wide and slightly raised. In the past, hence the spokesmen of the czars read their proclamations to the people. Here, the Orthodox priests placed an altar to make an open air cathedral of the square. At the stroke of noon, eight people, including a young mother, Natalya Gorbanevskaya, with a few month old baby in her arms, climbed the Lobnoye Mesto. They display banners such as, “shame on the occupiers”, “Hands off Czechoslovakia”, “we are losing our best friends”, “freedom for Dubček”.

The most incisive slogan in Russian says, “За вашу и нашу свободу”, transliterated “za vashu i nashu svobodu!”, translated “for your and our freedom”.

The peaceful demonstration offends the Party. It shows that not all of the Soviet people are inert, yielding and obedient, there are those who sympathize with Czechoslovakia, with the reforms of the Prague Spring, who would want the dream that is the “new direction” of Alexander Dubček to spread even in the Great Russia. In short, it is an intolerable demonstration. Five protesters are immediately put behind bars. Natalya avoids jail that day because she has her son with her. The Party grants her relative, brief freedom, but only until December 1969, when the State speciously declares her schizophrenic and locks her up in the chilly atmosphere of the mental hospital in Kazan, the ancient capital of the Tatars.

Who however is, Natalya Gorbanevskaya? She is a poet, a translator of Polish literature, and particularly a civil rights activist. It is a new term, a new task, to reveal the hypocrisy of the authoritarian communist law. Natalya is “a soft voice, a wild dove”, the words of one of her poems in 1963. In ‘68, aged 32, by the time August arrived she had already been noticed, among the small circle of dissidents, for having begun publishing a samizdat journal (as these self-produced underground publications were called) for a few months entitled “Chronicle of Current Events”, chronicles of injustice and unfair trials to critics of the permanent revolution. During the months of freedom following the demonstrations at Red Square, she helps circulate the texts with the story of the trial. By 1969 it is already a book, still as a samizdat, which is simply titled “Polden’”, “Noon”; the following year the text arrives in Frankfurt, where it is translated into English and French, under the title of “Red Square at noon”. Natalya however, is already in a mental hospital, where she remains until 1972. After her release, she escapes to Paris, in ‘75. Life in France consists of work as a translator from Russian and Polish, the collaboration with Radio Free Europe, the work in the editorial board of “Russian Idea”, with constant attention to the socialist bloc.

She and her companions, took to the streets in Prague, in a free, supportive, risky gesture. One of the many echoes of ‘68 Czechoslovakia in the continent, demonstrating the imaginative power of Spring.

The researcher and Bohemist Massimo Tria, in an article titled “The invasion viewed by the Soviets” (in the volume “Primavera di Praga, risveglio europeo”, edited by Francesco Caccamo, Pavel Helan and Massimo Tria, published in 2011), tells the stories of these long neglected heroes. His words echo those of Pavel Litvinov, grandson of the People’s Commissar Maxim Litvinov, the Soviet foreign minister who had to be replaced by Molotov as he refused to sign a pact with Hitler. Pavel was one of the “eight” from Red Square. The eight knew that there was no Dubček in the Soviet élite, but hoped that the Czechoslovakian reforms could spread further east: “we were hoping for a Moscow Spring”.

The cultural interplay between Prague and Moscow is much more complex than chapters on the history of the Cold War, or the current economic news on Russian properties in Bohemian towns. In the past years, there has been a continuous exchange of hidden ideas mutual support. When Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn was banned by the Soviets, he was read publicly and provocatively in Prague, in 1967 by the writer Pavel Kohout. Then when normalization came, the Muscovite dissidents relaunched the challenge with the samizdat. The “chronicles” founded by Gorbanevskaya alone produced 63 clandestine publications between 1968 and 1983. The dissidence in the form of samizdats, in turn, formed the basis of Václav Havel’s movement, Charta77. Tria still in his cauldron of historical sources, refers to the words of Larisa Bogoraz, a Ukrainian scholar, also among the “eight”, who remembers the liberating period of Mikhail Gorbachev’s Perestroika in the late eighties with a key observation: “that in Czechoslovakia everything happened faster, in a more radical and coherent manner”. What remains of a silent dialogue between oppressed people, who could only find a voice after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

So the figure of Natalya Gorbanevksaya was finally able to shine in the collective (we could say “European”) imagination. 2008, the forty year anniversary of those fateful events, was a key year: Natalya, with Havel and other dissident historians of the socialist bloc, in June signed the Prague Declaration on European Conscience and Communism. In August, the Czech prime minister Mirek Topolánek gave her a commemorative medal for her battle against the invasion, and in October the University of Lublin (in the meantime she has become a Polish citizen) conferred on her an honorary doctorate.

“Natalya Gorbanevskaya is a star, she is the activists’ icon for the defense of human rights”, were the words of Nina Belyaeva, Russian scholar of civil rights at the prestigious Higher School of Economics in Moscow. She places Natalya at the peak of her country’s activists, “just below Andrei Sakharov”. Not only as a classic image of the political dissident, but also as a woman, as a mother, a common thread that, for Belyaeva, connected her to new ways of being an activist in civil society, sometimes so far from the intellectual austerity of the “eight”, like the Pussy Riot experiment. Incidentally, the latter “are women much more smart and on the ball than the media usually represent”.

The lively Natalya, fought to the very end. In August 2013 she took part in a rally in memory of the same one 45 years earlier, once again in Red Square. Once again, the police intervened. Professor Belyaeva, however points out, that in this case there was no ideological clash with the Czechoslovak counter-revolution: it is modern Russia, with Moscow’s streets filled with policemen, who prohibits and punishes any unauthorized demonstrations. Gorbanevskaya wasn’t stopped, nevertheless it was her last demonstration in Red Square. Last October, there was again contact with Prague, when Charles University gave her a medal in honour of her life in defense of human rights, democracy and freedom. In the same few days, she stopped to greet the tomb of Václav Havel. She died aged 77 on the 29th of November, 2013, at her home in Paris.

by Giuseppe Picheca