In the endless possibilities of the digital age, we explore how the reporter’s job and the readers are changing even in this country

Forget the reporters with the simple notebook, and a pencil always resting on their ear; forget the waistcoats with eight pockets full of notes, photographs, rolls of film and recorders; forget, once and for all, investigative journalists of elegance and adventure like Dustin Hoffman and Robert Redford in “All the President’s Men”. The sharks of the editorial offices today, have their faces hidden by a smartphone.

It is journalism 2.0, the update of the profession in the digital era. We are not here to talk of surprises, for several years the technological revolution has deeply changed many professions. However, this sector, in particular, has certainly grown in a rather drastic way recently.

But what is happening in the Czech Republic? The School of Social Sciences of Charles University in Prague has recently contributed to the realization of the Digital News Report 2016, the annual report from the Reuters Institute at Oxford which records the state of the industry of digital information in the world.

But what is happening in the Czech Republic? The School of Social Sciences of Charles University in Prague has recently contributed to the realization of the Digital News Report 2016, the annual report from the Reuters Institute at Oxford which records the state of the industry of digital information in the world.

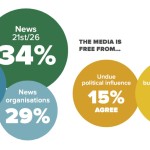

The study, as expected, confirmed the rapid rise of digital information even in the Czech Republic. The first clue is commercial, as in this country, in recent months, the “online” industry has reached the print media in terms of advertising market, about 20% of the total, while TV advertising still has the greatest share, with Česká Televize and TV Nova ruling the roost. As expected, if the web is growing, the press is in crisis. Advertising has decreased, as has the percentage of people who read daily newspapers or weekly publications (an already critical percentage, from 38% to 34%), while the number of those using social media to inform themselves has risen by ten points, to 51%, passing the mark towards the majority of the population. In total, 91% of Czechs use the Internet to inform themselves (against, for example, 83% of Italians).

The only data demonstrating that the Czech Republic is a bit “behind” compared to other countries, is in the use of smart phones to read the news, at 40% (for their Polish neighbours it is 58%), and with those who trust in digital information at 34%. It should be highlighted that only 13 in 100 Czechs say they agree with the statement “the media are free from pressures from the business world”. This is very clearly affected by the well-known concentration of national media in the hands of a few billionaires, most notably the vice premier Andrej Babiš, since 2013 the owner of two major daily newspapers and the main commercial radio station.

The advance of the “data journalism”

Research of this type is focused on the consumption of information, and prior to production the new customs must be optimized. Reducing digital journalism to social networks, however, would be a mistake. The technological revolution has in fact provided a new base for the creation of the news, as well as distribution. The field of “data journalism” is the result of the union between traditional journalism and cybernetics, statistics and web engineering. In short, when the analysis of complex data can lead to a story to tell. It was actually discussed in Prague last October 14, when the capital hosted an international conference on the subject, entitled News Impact Summit – Digital journalism practices: social media, data and best way to tell stories. Having been organized by the European Journalism Centre and Google News, it attracted journeymen to the city and those curious to hear information from all over Europe and beyond, with several speakers having come specially from the United States. There was some discussion of storytelling and new media, security and privacy, accuracy and views. The succession of speakers, the audience took notes quietly. Forget pen and paper, a hundred people with their fingers on small touchscreens, and only a few, out of fashion, resorted to the drumming rhythm of the keyboard of their laptop.

The Czech Republic was certainly a host highly interested in the subject. The country has proven in recent years, that it knows what’s what in the sector, and with a certain pragmatism, even if far away from the flow of capital of the Silicon Valley giants. Perhaps due to the skepticism of the Czechs regarding information on the payroll of duty magnates, the reliability of the numbers and science has a comfortable aura. There are more amusing or light examples, like riding in a car with GPS, and recording the disconnections of the land, or other more complicated ones, like how to manage archives with ten million files.

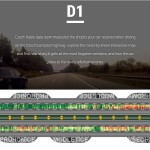

Two young journalists, Jan Cibulka and Marcel Šulek, for example have experienced how the passion for electronics can create the basis for the “sensor journalism”, based precisely on the electronic collection of information. An idea told through the megaphones of Český Rozhlas came from a daily annoyance: the terrible conditions of the D1 motorway between Prague and Brno. With a 15 euro kit consisting of a GPS sensor purchased online, duct tape and a smartphone, they managed to build a small accelerator that could “feel” the vibrations of the road. A Sunday return trip was enough to collect the necessary data and create a very detailed map (ten per second) of the motorway. Results? On the one hand, it is interesting to know that at kilometre 127 in the direction of Brno, between Velký Beranov and Měřín, there is a heavier vibration, a disconnection on the ground and at 100km/h, 0.2 seconds, loading a pressure of 16G (sixteen times the Earth’s atmosphere) on the rear wheels (in short, you have to go easy!). On the other, such detailed knowledge of the conditions of transport, made public, become an instrument of “democratic” pressure and measurement on proceedings, referrals, concessions and delays. In short, a simple and popular topic treated with good journalism, still available by clicking on the article “How bumpy is the Czech Highway D1?” on the radio website.

Panama papers and a Czech connection

Czech excellence in data journalism has Pavla Holcová as a spokesperson, the Czech Centre for Investigative Journalism (České centrum pro investigativní žurnalistiku), the only one in the country which is part of the international union to which the cybernetic folders of the “Panama papers”, the biggest financial scandal of recent years, have been entrusted. More than eleven million documents of the company Mossack Fonseca, 2.6 terabytes of files related to more than two hundred thousand offshore companies, a huge digitized file that keeps journalists from all over the world busy for months. Holcová and her team have taken up the task of searching for information regarding the company and Czech businessmen. A centre of enthusiastic investigators at the service of the truth, which up to now, has identified a little less than 300 Czech clients of the Panamanian company, connected to the country via the local eBanka, which is now closed. A Czech connection of tax evaders, lobbyists and diamond traffickers, such as Radovan Krejčíř, probably the “most famous criminal of the country”, arrested in South Africa in 2013. A first report was published by the centre already last spring, in English on the OCCRP website, Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project.

In the endless possibilities of the digital era, journalism 2.0, both at Czech and international level, has the balance between business and quality imposed on it, and between marketing and information. If international readers are skeptical about the new media, the Czechs take this skepticism to an excessive level. The solution seems to be this: reliable and quality journalism. If possible, with concrete data.

by Giuseppe Picheca