The Belgian and European capital was historically the centre of international espionage. Old affaires are emerging which lead back to pre-1989 Prague

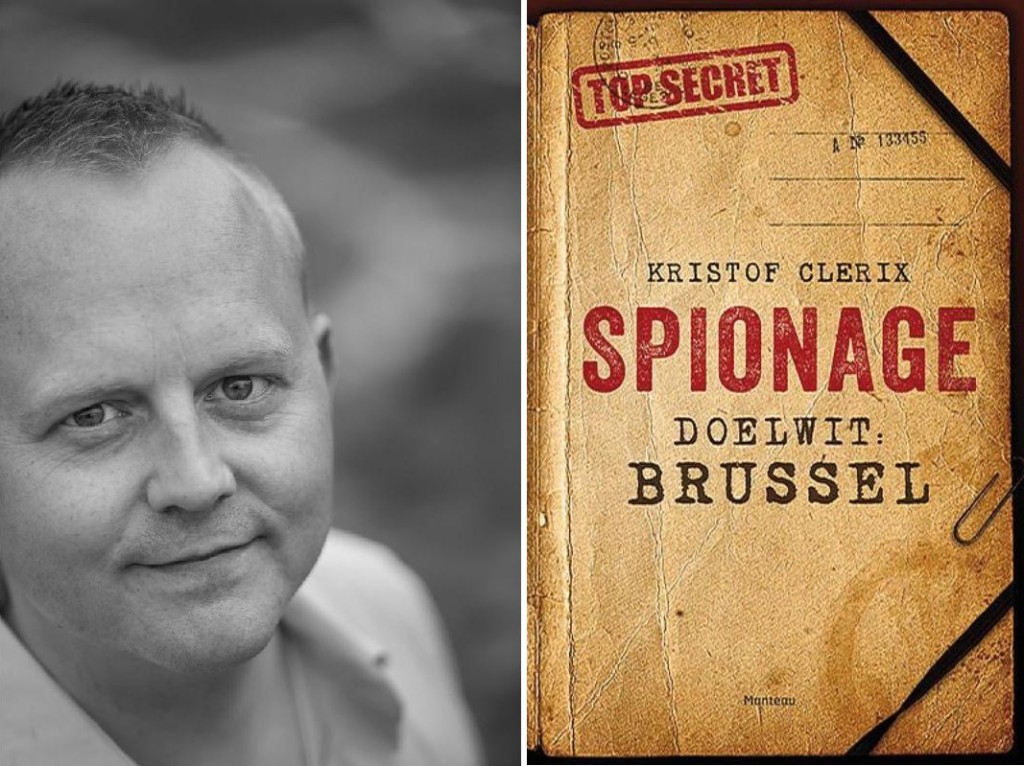

A book by journalist Kristof Clerix tells stories of Eastern European spies during the time of the Cold War

High collar trench coats, wide-brimmed hats, long shadows and black and white photos. It is hard to escape the stereotypes of the old tales of espionage during the Cold War, all too fascinating, well-known, and even pleasant in their narrative, to abandon. Any self-respecting spy story has to be told this way. The setting then has its places of worship: Orson Welles chased by the camera in the immediate post-war Vienna; Richard Burton, the spy who came from the cold, under the barbed wire of the Berlin Wall; not to mention the cities that have made their charm out of the mystery, like Venice, Marseille, Istanbul.

In the simple categorization of the spy story scenario, a town best known for being the “capital of bureaucracy” like Brussels, does not raise an immediate interest.

In the simple categorization of the spy story scenario, a town best known for being the “capital of bureaucracy” like Brussels, does not raise an immediate interest.

That said, it is indeed in Brussels, where European political modernity conserves a treasure of information that would make the mouth of any secret agent water. Hundreds of diplomatic seats, inter-governmental offices, NGOs, thousands of corridors full of officials. For example, there are 24 kilometres of corridors under the glass and steel of the Justus Lipsius building, the seat of the Council of the European Union. In the city all the classic disguises of espionage are available: journalists, diplomats (over 5 thousand in the city, more than Washington or Geneva), officials, lobbyists.

“NATO and the EU have turned the Belgian capital into the Berlin of the 21st Century”, wrote the Brussels correspondent of a famous Italian newspaper (la Stampa), a few years ago.

The process of centralization of power towards the city was gradual, from the birth of the European institutions moving forward. Yet it was the Atlantic Pact that enticed prying eyes. The forced relocation, in 1967, of the NATO headquarters from Paris (at the time of the withdrawal from the organization by De Gaulle’s France) to the Brussels suburb of Haren, gave it a decisive boost. Traveling backwards in time to these origins in Brussels the “nest of spies”, the Flemish journalist Kristof Clerix went searching for its secrets, publishing the book “Spionage. Doelwit: Brussel” (“Espionage. Target: Brussels”) in 2013. For this type of dossier, the story has provided a huge source: the opening of state archives of the communist regimes. At the dissolution of the Iron Curtain the confirmation arrived that the services of the Warsaw Pact had “their men” under the Atomium. It was thought that there were between 40 and 45 spies of the KGB, who were walking around the city in the mid-eighties, and even up to 134 agents of the East German Stasi. It was from these stories that Kristof also fished out some affaires from Czechoslovakia.

Men of Prague under the elegant buildings of the Grand Place, in the slums behind Gare du Nord, in the hardly reassuring shadows of the long Elisabeth park, that hasten the pace of those who want to reach the Basilica of the Sacred Heart. In the late eighties the Czechoslovak embassy in Brussels, rue Adolphe Buyl (today the Czech Embassy), was located in a building of very clear geometry, with six large windows on each floor, built for the great Expo ‘58; the building held seven spies of the Státní Bezpečnost (Czechoslovak security services, StB) under diplomatic cover. These included Jan Braňka, specialized in propaganda, who was the “manager of public relations”. The man with the codename: Agent Krupka, born in 1936, with “brown eyes, curly, black hair, and a gendarme-style moustache”, had arrived in the city in 1985, as press secretary of the embassy. His task was to influence foreign journalists, the public opinion, bring the peace movements together, even to woo certain politicians and their discourses into his own line of thinking. Everything was set up to put the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic in good light. “In the world of espionage, these activities were called active measures”, the journalist explains. “The Czechoslovak services showed a strong interest in the Belgian journalists. The spies organized meetings in the restaurants of Brussels, taking advantage of the interest of the bars to reach official contacts”.

In November 2010, in Prague, Clerix visited the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, accompanied by a reporter from the Czech daily newspaper Právo, who helped him in translation. “A real blessing for a journalist in search of interesting stories”, said Kristof himself. “The advantage to Prague was that none of the data entered in the file was deleted by a marker, as was the case on the other hand, in the archives of other countries. I could use all the material collected, clearly after the necessary evidence, for example, hearing the people mentioned. The Czech institutions have been very kind, open and helpful. The institute gave me a CD with 26 thousand documents related to Czechoslovakian espionage in Belgium”. In addition to spending endless hours flipping through documents, Clerix has had the opportunity to meet Jan “Krupka” Braňka, and then tell episodes of the life of a Bohemian secret agent with full presumption of truth. Like the winter mornings on the tram 71, with seats occupied by spies waving different flags, meetings in prestigious cafés with Kafka-loving reporters, chases through the streets of the centre with strangers in trench coats and leather gloves. An example of the work of Krupka is in his relationship with the former senator Jean Jacques Verstappen; a known politician, of the ranks of the Belgian Communist Party, an editor of the pacifist “Rencontres pour la Paix”. The ex-senator and the StB agent met more than fifty times. Besides confidential information, Braňka gave Verstappen more than a hundred thousand francs to support the costs of the magazine and directed it to the interests of the Warsaw Pact.

In November 2010, in Prague, Clerix visited the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, accompanied by a reporter from the Czech daily newspaper Právo, who helped him in translation. “A real blessing for a journalist in search of interesting stories”, said Kristof himself. “The advantage to Prague was that none of the data entered in the file was deleted by a marker, as was the case on the other hand, in the archives of other countries. I could use all the material collected, clearly after the necessary evidence, for example, hearing the people mentioned. The Czech institutions have been very kind, open and helpful. The institute gave me a CD with 26 thousand documents related to Czechoslovakian espionage in Belgium”. In addition to spending endless hours flipping through documents, Clerix has had the opportunity to meet Jan “Krupka” Braňka, and then tell episodes of the life of a Bohemian secret agent with full presumption of truth. Like the winter mornings on the tram 71, with seats occupied by spies waving different flags, meetings in prestigious cafés with Kafka-loving reporters, chases through the streets of the centre with strangers in trench coats and leather gloves. An example of the work of Krupka is in his relationship with the former senator Jean Jacques Verstappen; a known politician, of the ranks of the Belgian Communist Party, an editor of the pacifist “Rencontres pour la Paix”. The ex-senator and the StB agent met more than fifty times. Besides confidential information, Braňka gave Verstappen more than a hundred thousand francs to support the costs of the magazine and directed it to the interests of the Warsaw Pact.

What is interesting about the Cold War stories, it is that they can teach espionage mechanisms which are still in use today. “The use of this “human intelligence”, or work with informants”, says Kristof, “is revealed in detail: how these sources are searched, recruited, manipulated and managed. Today services around the world still use “human intelligence”, from the interception of telephone calls to the internet traffic control”. Not only that, he emphasizes, “Brussels is still a battlefield regarding information. It is enough to think of the ways in which the Ukrainian conflict is told in terms of “public relations” on both sides”. The city only tries to boost its own strategic importance, both on the economic front (de facto capital of Europe) and the military front (NATO has come back to being the cornerstone of the security policies of the geopolitical “North”). So much so that in November 2013, the Commissioner for Justice Viviane Reding, launched the proposal (in the end unheeded) of a European “CIA” in Europe, able to join the secret services of the EU and strengthen the security policy.

While rereading Krupka agent methods today, which included illegal financing and media pressure, there are few surprises, as accustomed as we are to the dynamics of “lobbying” business. Media management is critical, and who knows how many Krupkas from different nations roamed around the city. A January 2015 report on “mass espionage”, presented by Austrian MEP Paul Rübig (People’s Party), urged all MEPs to turn off their smartphones, and also take out the batteries before starting office work. This is because they could be used as remote control “bugs”, at least according to the Conservative MPs. Conspiracy theorist phobias or wise caution? Of course in Brussels the doubt often returns, traveling on trams full of officials in grey jackets, listening to those excerpts of French with strong foreign accents…

by Giuseppe Picheca