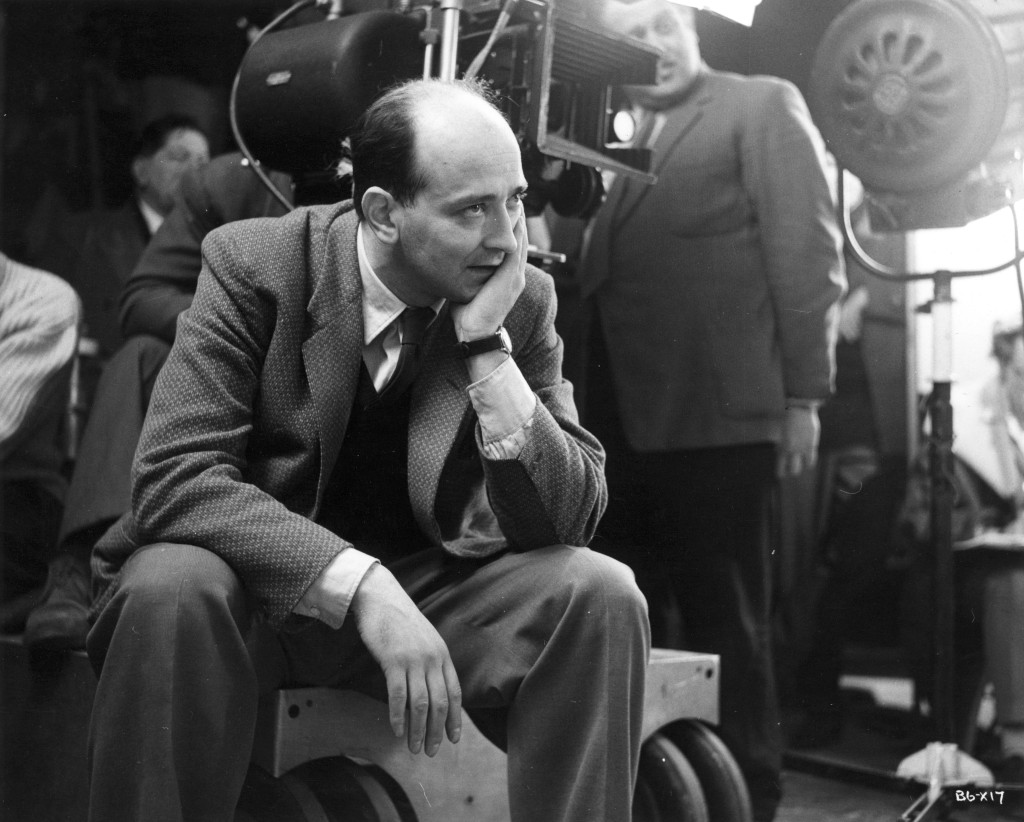

The exceptional life of Ostrava-born director, who emigrated to England in the early days of the Holocaust, before becoming one of the founders of English Free cinema, then a symbol of American cinema of the 70s and 80s

A master of international stature, who until a few years ago was almost unknown among his countrymen. We are talking about Karel Reisz, who along with Miloš Forman, is perhaps the most significant Czech film director of all time, a great man who had the curious destiny of never having worked in his country of origin.

Karel was born in Ostrava in 1926, leaving Czechoslovakia in 1939, when his father, a wealthy lawyer of Jewish descent, decided to send him to safety alongside his older brother Pavel, putting them on a departing train to Britain, away from the growing Nazi threat and the horror of the Shoah. The trains of salvation were those of the legendary Kindertransport operation, organized shortly before the outbreak of the war, by the British philanthropist Nicholas George Winton.

After completing his studies at a school in Reading (50 km from London), and a brief spell in the Royal Air Force, once the war was over he returned to his homeland to find out the fate of his parents and family members, all of whom had been exterminated in Auschwitz. Hence the decision to return to his new home, and to settle in England, where he graduated in chemistry at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and then teaching at the Grammar School in Marylebone, before becoming a journalist.

His real dream, however, was cinema. He first began writing reviews for the magazine of Oxford University, Sequence, alongside Lindsay Anderson and Galvin Miller, and subsequently for Sight and Sound, the most renowned film magazine in the UK. With Anderson he would form a long-lasting creative collaboration, first as journalists, then as colleagues behind the camera.

Reisz became known with the book Technique of film editing, a fundamental text, used by future masters of cinema such as Truffaut and Resnais, but his passion and desire to create, bore its first fruit when he began making short films, with the support of the Experimental Film Fund of the British Film Institute. As a result, he helped create, along with Lindsay Anderson and Tony Richardson, without forgetting the Italian writer and director Lorenza Mazzetti, Free Cinema, a movement not limited to film, but also a cultural and social one. The viewpoint was clearly left-wing, with the implicit theme of believing in freedom, in the importance of the individual, and in the meaning of everyday life.

Reisz became known with the book Technique of film editing, a fundamental text, used by future masters of cinema such as Truffaut and Resnais, but his passion and desire to create, bore its first fruit when he began making short films, with the support of the Experimental Film Fund of the British Film Institute. As a result, he helped create, along with Lindsay Anderson and Tony Richardson, without forgetting the Italian writer and director Lorenza Mazzetti, Free Cinema, a movement not limited to film, but also a cultural and social one. The viewpoint was clearly left-wing, with the implicit theme of believing in freedom, in the importance of the individual, and in the meaning of everyday life.

His early works consisted of documentary films, like Momma Don’t Allow (directed by Reisz and Richardson), before getting to the key films of the movement, in particular a turning point in British cinema: Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1961).

Up until the release of the Silesian director’s masterpiece, British cinema had virtually ignored the life of the working class, previously represented only by secondary characters, and never protagonists. Saturday Night and Sunday morning, however, the first feature film by Reisz, shocked the audience with its coarse language and the explicit depiction, at least for the time, of the extramarital affair between the protagonist Jimmy, a factory worker, and the wife of his friend. A sharp, sociologically and politically accurate work, which enjoyed an extraordinary success among both critics and the public, also launched the career of leading actor Albert Finney. Curiously, it took a foreigner to revitalize and change the trends of British cinema, as well as creating one of the most significant films movements of the time, along with the French New Wave, and the Czechoslovak and Polish new waves.

It was the beginning of the first golden era of his career, and the films Night Must Fall (1964), again with Finney, Morgan! (1966), and Isadora (1968) followed. It was particularly in Morgan!, where the true genius of the filmmaker was present, with a storyline that follows an eccentric, unrestrained man who tries to win back his wife to avoid divorce. He uses all means possible, even dressing up as a gorilla, creating chaos everywhere. The main star of the latter film (and also Isadora), Vanessa Redgrave, won the Best Actress award at Cannes, but the commercial failure plunged the author in a long period of silence.

When he resumed his activity in 1974 however, it was in the United States, where he hoped to embark on more ambitious projects. Reisz did not hit a wrong note in his American debut, The Gambler, featuring one of the best performances in the career of star James Caan, in the role of an English professor in New York, much loved by his students, who fights against a gambling addiction, ending up in a desperate situation due to a large debt. His second American adventure was the equally effective, and edgy Who’ll Stop the Rain (1978), based on the novel Dog Soldiers by writer Robert Stone. Reisz again displayed his skill in directing actors, drawing an excellent performance from star Nick Nolte, in one of the many key films of the decade related to the Vietnam War, boosted by tension consisting of the constant threat of danger and numerous twists.

Although he had already obtained a certain degree of esteem and fame, his biggest international hit was The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1981), a melodrama based on the novel by John Fowles, and written by Harold Pinter, starring the already renowned Meryl Streep, and the emerging star Jeremy Irons.

If subsequent works marked his decline, Reisz however, had already helped to exert a decisive influence on the history of cinema, especially in England, where he laid the foundations of the future of the national cinema, and the conditions under which directors such as Ken Loach and Mike Leigh emerged later.

What is surprisingly, however, is the lack of attention paid to his filmography in his homeland, that is, at least until his death on November 25, 2002. The master filmmaker has also been rediscovered thanks to the documentary Karel Reisz, ten filmový život, directed by Petra Všelichová in 2012, and broadcast on Česká televize. An hour long, it retraces his life from his tragic childhood, and includes a series of illuminating interviews with co-workers, children and especially with his brother Pavel in Ostrava, where he returns to talk about their carefree childhood in the city known as the “Steel heart of the Republic”. There are plenty of anecdotes about his early days in England such as his reluctance to change eating habits, and refusal to Anglicize his name from Karel to Charles as his mother suggested him to do in the Prague station, the last time she saw him, before his farewell.

But the trump card of Reisz was precisely that; he was too Czech to be English and almost English to be Czech, and his origins gave him a unique insight into the places where he lived and worked, whether it was England or in the United States.

Those who had the good fortune to work with Reisz spoke of an English refinement, but also of a “meticulousness that was more typically Czechoslovakian”, as Vanessa Redgrave stated following his death. In hindsight, we see that a common thread in his works was the tendency to use rebellious protagonists unable to follow the dictates of society, a theme also present in several Czech films of the Nová Vlna at the time. We can therefore see Reisz as a kind of bridge, or link, between the Western cinema, and the Eastern European cinema, at the time of the Iron Curtain.

by Lawrence Formisano