The Centre against terrorism and hybrid threats has been set up ahead of the October elections. But for President Zeman, it is nothing more than an organ of censorship: “No one has a monopoly on truth”

As in the days of the Cold War, Prague is back on the front line against the threat coming from Russia. A virtual threat, however, made up of words, sharing posts, social networking and fake news. There are those who accuse the creators of false news for losing the election, as in the US presidentials, those who fear hacker activity so much in the paper ballot count that they have decided to return to the old system of counting of votes by hand, look at Netherlands, those who launched a network of 16 newsrooms in partnership to check the news, as in France, those who launched a system together with Facebook to identify the fabrications, as in Germany, those who have created an actual taskforce to combat the phenomenon. It is precisely the Czech Republic who is the leader of this battle, also in view of the German and French elections, as well as those in the Czech Republic in October.

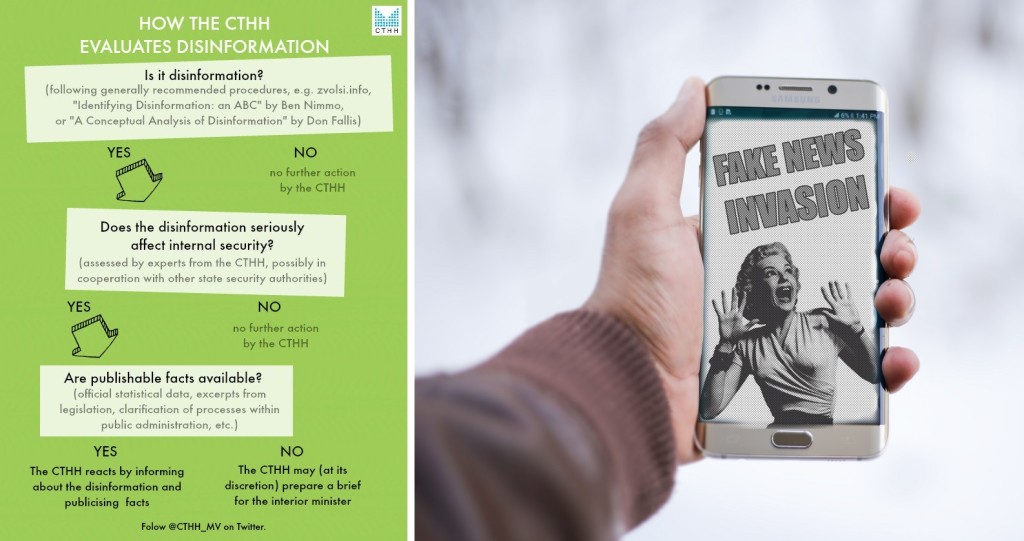

In Prague last December the 15th, specialists started the so-called “information war”. It is the start of the Centre against terrorism and hybrid threats (CTHH) created by the Czech government with the aim of identifying, exposing and stopping fake news, especially those considered to have been created by the Kremlin to influence the presidential vote, and Czech politics. An idea that will be copied soon also by Germany and Finland, according to much of the international media. At the head of this special unit, is Benedikt Vangeli who made the battle against misinformation and the circulation of false news his, as well as fighting click-baiting on social networks, and on the Internet. It is not only about tracking the websites created ad hoc, as happened in Macedonia to create false news about Hillary Clinton, but also check the videos circulating on the network, with titles deliberately chosen to create alarmism, fear, disillusionment, scandal. This indeed was the case with the shocking video posted and shared in December from the website and Facebook page “Never again Canada” which showed a group of boys beating a woman. In the title, it was emphasized that a group of immigrants were responsible, but it turned out to be a fake. A manager of the Czech Police, David Chovanec, recognized that video, which dated back to 2016 and had been filmed by a surveillance camera in Prague. The young people were not migrants, but Czech citizens, one of whom had already been convicted. It was precisely the CTHH which destroyed the case, with the first success since its creation. The aim of the unit is “to coordinate the preparation of the elections in order to minimize the dangers. We will closely check what happens in France and Germany, where in spring and September elections are scheduled, respectively, and we’ll see what we can learn”, explained a source from the unit, “while we will also instruct public officials to avoid giving in to blackmail by email or by lobbyists”.

In Prague last December the 15th, specialists started the so-called “information war”. It is the start of the Centre against terrorism and hybrid threats (CTHH) created by the Czech government with the aim of identifying, exposing and stopping fake news, especially those considered to have been created by the Kremlin to influence the presidential vote, and Czech politics. An idea that will be copied soon also by Germany and Finland, according to much of the international media. At the head of this special unit, is Benedikt Vangeli who made the battle against misinformation and the circulation of false news his, as well as fighting click-baiting on social networks, and on the Internet. It is not only about tracking the websites created ad hoc, as happened in Macedonia to create false news about Hillary Clinton, but also check the videos circulating on the network, with titles deliberately chosen to create alarmism, fear, disillusionment, scandal. This indeed was the case with the shocking video posted and shared in December from the website and Facebook page “Never again Canada” which showed a group of boys beating a woman. In the title, it was emphasized that a group of immigrants were responsible, but it turned out to be a fake. A manager of the Czech Police, David Chovanec, recognized that video, which dated back to 2016 and had been filmed by a surveillance camera in Prague. The young people were not migrants, but Czech citizens, one of whom had already been convicted. It was precisely the CTHH which destroyed the case, with the first success since its creation. The aim of the unit is “to coordinate the preparation of the elections in order to minimize the dangers. We will closely check what happens in France and Germany, where in spring and September elections are scheduled, respectively, and we’ll see what we can learn”, explained a source from the unit, “while we will also instruct public officials to avoid giving in to blackmail by email or by lobbyists”.

That the threat of hackers and fake news speak Russian, is something concerning which there is little doubt for Jakub Janda. The deputy director of the think tank based in Prague, European Values, also known as Kremlin Watch, states there are dozens of sites in Czech language which create and distribute news which is exaggerated or completely false.

In the Czech Republic, there are three main objectives of these sites: to attack the politicians critical of Russian aggression in foreign policy, such as in Ukraine, to support politicians who have pro-Moscow attitudes and positions and undermine the long term EU membership of the Czech Republic. The big problem is that according to recent polls, 26% of Czech citizens believe these sites, and read them on a daily basis. “The main objective of the propaganda in the Czech Republic is to insinuate doubt in public opinion that democracy is not the best way to organize a country, to create a negative image of the EU and NATO and to discourage people from participating in the democratic process” said Secretary of state for EU Affairs Tomáš Prouza.

And if it remains difficult, if not impossible, to identify who is behind the fake news, who writes it, spreads it, and finances it, it is even harder for the CTHH to withstand the attacks from the man in the highest position in the country, the avowedly pro-Kremlin President Miloš Zeman. For the head of state “no one has a monopoly on truth”: “If you have a point of view, for example, and the Russians have points of view, and you want to formulate them publicly in the media, it is not misinformation, it is not propaganda”. This is the president’s position, defending his statements which often seem too close to Moscow, and that also earned him New York Times headlines, according to which Zeman is on the payroll of the Kremlin. The analysis of the Stars and Stripes newspaper was clearly branded as a lie by Pražský hrad, but for the New York Times, Russia, besides hacker attacks and fake news, has not given up the old and traditional way to influence the policies of other countries: lavish funding, such as Lukoil’s to the campaign of the head of state.

Zeman, therefore hit where it hurts, called the unit against fake news and web terrorism a genuine censorship tool that takes the Czech Republic back to the pre-89 period (comparing CTHH to ČUTI, Československý úřad pro tisk a informace, the Czech authority for press and information, the old regime’s control and censorship body), a position openly condemned on the other hand, by Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka who has shown support for the task force.

In Prague even the Russian intelligence presence invokes fear, and are “the most active foreign intelligence services” in the Czech Republic, according to the Czech agency for internal security (BIS), according to which the primary objective is “fabricating misinformation” with the slogan that “everyone lies”. According to the Czech intelligence the number of Russian diplomats is twice as high than the US, and between them may hide several spies.

And that the terrain of the struggle against terrorism and global destabilization in general has moved to the web and social networks, however, remains clear. The signals are interpreted as clear even among the newest generation: a group of students from the Masaryk University in Brno last year launched the project “Zvol si info”, which aims to “raise awareness of the importance of increasing the media literacy among young Czechs”.

by Daniela Mogavero