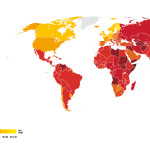

The Czech Republic has improved of 16 positions in the International Transparency Index on corruption, but a lot remains to be done. The Council of Europe this year has ruled that the measures taken by the Czech authorities in their fight against corruption are still not adequate

The Czech Republic is the investors’ paradise. Although a few of the major foreign partners, especially the Germans, tend to openly turn up their nose at the widespread corruption and irregular adjudication of public tenders, the situation seems to have improved in the last period. Reporting on this trend is the latest world ranking index on perceived corruption, prepared by Transparency International, which shows a marked improvement of the Country. Prague ranks in 37th position this year, 16 positions higher than last year, when it stood alongside such countries as the Seychelles, Jordan and Namibia, with Italy in 61st position (69th in 2014).

“For the Czech Republic, this is one of the most significant improvements at international level and is surely the result of the hard work of the last few years”, according to Radim Bureš, director of the Prague Transparency International branch. In his opinion, the first real positive changes, paradoxically, came about with the legislative reforms initiated by the former Nečas government, that was also involved in a sensational corruption story in the early summer of 2013.

Even the current government has set public morality at the forefront of its program. The intentions are good and a certain amount of progress has actually been made, Bureš pointed out, but without failing to highlight the slowness of the Czech Parliament in taking legislative measures to cope with the issue. The representative of Amnesty has also underlined the anomalous position of Vice Premier and Finance Minister Andrej Babiš, “whose conflict of interest is evident to everyone, even to his own voters”.

In short, it is still too soon to say whether the battle has been won. Besides, if you analyze the Transparency index at European level (and not global), the Czech Republic still ranks in 22nd position (three more than last year), therefore, in the same category as the most problematic states. Actually, the improvement achieved in the last 12 months is rather faint if we compare it to the rating of other Western countries, where the average is 67 points (compared to the 100 available), and Czech Republic gained 56 points.

In short, it is still too soon to say whether the battle has been won. Besides, if you analyze the Transparency index at European level (and not global), the Czech Republic still ranks in 22nd position (three more than last year), therefore, in the same category as the most problematic states. Actually, the improvement achieved in the last 12 months is rather faint if we compare it to the rating of other Western countries, where the average is 67 points (compared to the 100 available), and Czech Republic gained 56 points.

Prague has surely made a significant step forward in just over a year, but in hindsight, the amount of progress has not been impressive enough to overshadow the years of the big scandals, such as the Blanka tunnel scandal (whose construction was subject to long delays and unprecedented increases in costs), the European funds muddle and the unresolved mysteries regarding large scale state privatizations events date back just a short time ago. “The uncompromising fight against all forms of corruption and serious financial crimes are fundamental priorities of our government policy”, Prime Minister Bohuslav Sobotka has stated on a number of occasions and who, since Amnesty’s last assessment, has asked observers to wait a while before giving credit just to the index figures, and obviously aware that further measures still have to be taken.

As we have already stated, even the Nečas government has placed the fight against corruption among its priorities. However, its credibility ended with the dramatic downfall in June 2013, when Jana Nagyová, head of the prime minister’s cabinet and his mistress, was arrested. As well as Nagyová, who has now become Mrs Nečasová, also other prominent personalities of the Czech political and financial world were arrested during those very tense days back in 2013. But above all, the investigation focused on the so-called “godfathers of Prague”, the businessmen and lobbyists Roman Janoušek and Ivo Rittig, suspected of being involved with the criminal world that for many years had characterized the management of public affairs in the Czech capital. An unprecedented scandal and a wave of arrests that not only shook the conscience of those who were involved, but also had a strong impact on public opinion.

However, even under Nečas, certain measures had been taken. For example, during his government term, Lenka Bradáčová was appointed Director of the Prague Public prosecutor’s office, a magistrate of sterling character, nicknamed “lady Commissioner Cattani”. Ms Bradáčová proved to be quite uncompromising and unwavering, as in 2012 when she ordered the arrest of David Rath, governor of Central Bohemia, former health minister and member of the Social Democratic party (ČSSD), the classic untouchable, who was caught red-handed with a bribe of 7.5 million crowns, around 300 thousand Euro, which he had just pocketed from a scam against the European Union. Bradáčová, “lady testosterone”, as her detractors call her, seems to have brought a boost of energy in recent years, or at least, she seems to have taken the right steps against corruption.

Another symbolic character in Prague in the battle against malpractice is, perhaps, Ondřej Závodský, a jurist and since 2014, Deputy Minister of Finance, responsible for the management of state assets. His is a story of its own. Blind since birth, Závodský received an award in 2011 from the Nadační fond proti korupci foundation, for his commitment against corruption. When he was just an ordinary clerk at the Interior Ministry, he decided to report a series of wrongdoings and clear acts of corruption on granting tenders by the public administration. A hard battle that was pursued with great difficulty and that led to mobbing attempts. While carrying out his task, he received threatening phone calls and anonymous letters. However, he remained steadfast in his pursuit, and after being degraded, his story ended up in the newspapers and eventually drew the attention of the foundation of the young tycoon Karel Janeček, another protagonist in the fight against malpractice. His Nadační fond proti korupci has organized a number of moralization campaigns in recent years but has also conducted inquiries, collecting evidence and documents on rigged public tenders. Much still remains to be done, such as a register for lobbying activities, which would help to bring to light the shady affairs of this sector, as Transparency has pointed out. Besides, it is often the Czech companies themselves that are calling for greater transparency. According to a survey carried out by Deloitte involving a hundred companies, businesses are starting to pay greater attention to anti-corruption legislation: if two years ago, only a fifth of them were in favour of introducing a code of ethics, in 2015 that number had risen to nearly 75%. A result that is also linked to the fact that four years have passed since the penal liability of legal persons came into force.

The new legislation, which is about to be approved, also includes the conflict of interest and transparency of political party financing, as well as greater protection for the whistleblowers, namely those individuals who, in the interest of the public good, report illicit behaviour occurring in the organization in which they are employed, whether public or private.

Despite the recent progress made by the Czech Republic, to remind us that “all that glitters is not gold” is also the opinion expressed this year by GRECO (the anti corruption monitoring body of the Council of Europe), which stated that the measures taken by the Czech authorities to fight corruption and assure transparency of party funding are “overall insufficient”.

by Daniela Mogavero