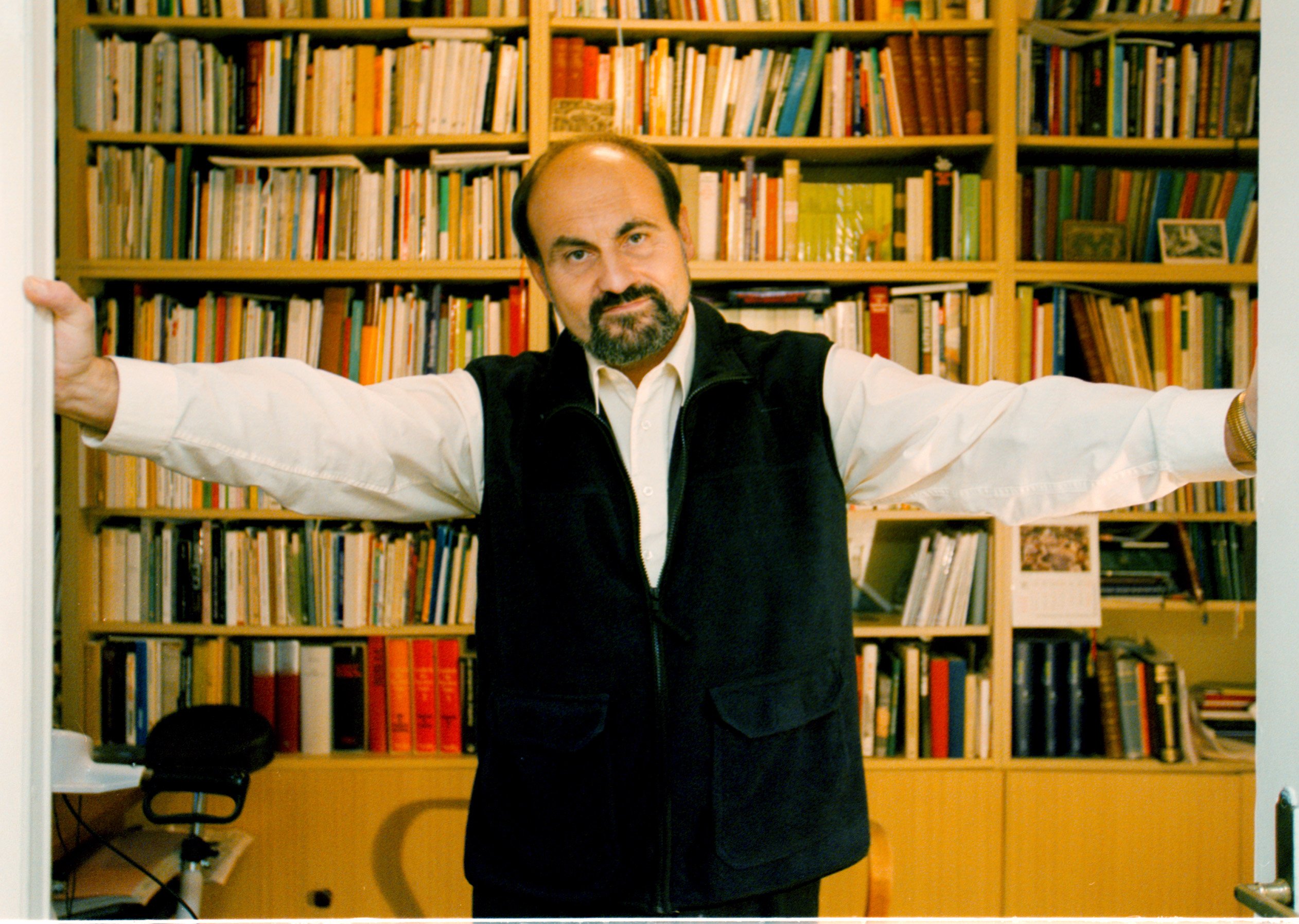

Priest, professor, writer and absorbed in the political situation of his own time, Halík is the best known intellectual Catholic in Czech Republic

“I try to communicate with those who search after truth, to show them that the Christian faith is not an ideology”. Czechs have a reputation for being atheist by definition, and being a priest in this context “is a fascinating opportunity, a wonderful mission and a tremendous challenge”. A challenge that Halík has won, as shown by the numerous awards that he has received for his intercultural and interreligious dialogue – and his appointment as consultant to the Pontifical Council for a Dialogue with Non-Believers, set up by Pope John Paul II. He teaches philosophy and sociology at the Charles University, but his activity goes beyond teaching and parish activity: he collaborates with a number of specialist magazines and writes about political and economic issues, besides being involved in civic and charitable initiatives. He is also a member of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts, and various national and international scientific associations.

“I try to communicate with those who search after truth, to show them that the Christian faith is not an ideology”. Czechs have a reputation for being atheist by definition, and being a priest in this context “is a fascinating opportunity, a wonderful mission and a tremendous challenge”. A challenge that Halík has won, as shown by the numerous awards that he has received for his intercultural and interreligious dialogue – and his appointment as consultant to the Pontifical Council for a Dialogue with Non-Believers, set up by Pope John Paul II. He teaches philosophy and sociology at the Charles University, but his activity goes beyond teaching and parish activity: he collaborates with a number of specialist magazines and writes about political and economic issues, besides being involved in civic and charitable initiatives. He is also a member of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts, and various national and international scientific associations.

He was introduced to the Catholic religion when he was still young: his parents were not believers but always celebrated Christian holidays. From his uncle, instead, he developed a passion and admiration for Jan Hus, a preacher and religious reformer, condemned for heresy and who was burned at the stake in 1415. During his studies, he devoted much of his time to this historical figure in an attempt to rehabilitate his reputation.

His interest in politics led him in 1967 to found a club at the University for discussions and debates, where he met Václav Havel, who was invited to take part in one of the debates during the Prague Spring. This led to a deep friendship that was to last over forty years. At the time, when Havel was President, Halík collaborated with his circle of aides as an external counsellor – to the extent – that Havel recommended him as his possible successor. Halík took into consideration the idea of becoming more involved in politics several times, but then gave up this hypothesis. “I believe that for the moment, my present involvement with students, at a pastoral and academic level, combined with my civil commitment as an independent intellectual, with an occasional public debate, is ideal for me”. However, this did not prevent him from commenting on political issues. In fact, at the end of 2011, a heated dispute broke out between him and Klaus who, according to Halík, was not sincere when he promised that the confiscated property during the Communist regime, would be returned to the Church. In response, at the Castle, they insinuated that Halík was not even a priest but “only an activist of Havel”.

During the invasion of 1968 he was in England, but soon came back; the death of Jan Palach convinced him that he should stay and fight against the regime. He was prohibited from teaching, because he dedicated his graduation speech to truth, rather than thanking the Communist Party. With a University degree he could not enter the seminary, so the only alternative was for him to join the clandestine church. It took almost ten years of preparation in a state of utmost illegality. He decided not to sign Charter 77, but without explaining why: he still had a year before being ordained priest, and if he been a signatory, he would have been subject to scrutiny. However, he was secretly ordained priest in 1978.

He continued to be involved in cultural and religious dissent, and for eleven years, he unlawfully held the office of priest, and at the same time, that of psychotherapist in a centre for alcoholics and drug addicts. He had always desired to combine his priesthood with a secular profession. The Christmas Mass of 1989 was his first public ceremony, then he became rector of the Church of San Salvatore, and in 2008 Pope Benedict XVI appointed him Monsignor.

After 1989, he began to travel around the world to hold lectures and even took part in an expedition to Antarctica. He met many historically famous people, such as the Dalai Lama, Mother Teresa and John Paul II.

Monsignor Halík is a chaplain of the University students in Prague and his masses are very popular and many are the youngsters who have been christened thanks to him. On Sunday, 20 January, during a mass, a commemoration took place in memory of Jan Palach. The church was crowded and many people of all ages took part. Halík entered the procession together with a group of students. He had a rather stern look on his face, but soon gained the sympathy and attention of the faithful when he starting speaking with his calm but confident voice, and a few quips. The homily was dedicated to Palach. Many people had condemned his self-immolation, but Halík, who had organized his requiem more or less forty-four years before, said by taking up the words of the writer Gilbert K. Chesterton “a person who commits suicide despises life, a martyr is he who despises death. And I believe that Jan Palach was like one of those martyrs – and went on to say. – He has responded to a divine call from God”. Palach did not reject the gift of life, but he sacrificed his own life for others. “With his gesture, he gave society a great sense of self-confidence and an awareness of its true values. I believe this is the real sense of Palach’s sacrifice”. Clearly, he did not change history and the Soviet troops were not stopped in their advance, but he was able to make his countrymen understand the sense of his gesture: that we must not submit or accept compromises, but must fight for freedom and democracy with great spiritual strength and moral integrity. In times of hardship, even Halík often pondered over that “fiery outcry: You must not submit! Because by doing so, you will desecrate and void the sense of his sacrifice and, in a certain way, Palach’s deed had a bonding effect”. Then, Halik went on to stress the fact that we are constrained by this act, and have to treasure it – not only was it an act of courage, but also “a gesture of love towards his people, because this young man had given greater value to the fact that his people should not submit, than to own life”. Palach, Masaryk and Havel are all bonded by a mutual love for their Country and a profound sense of responsibility towards their people – for this reason, their lives are an appeal, to which, we cannot remain indifferent.

Before dismissing his congregation, Halík expressed a few words on the recent presidential elections won by Milos Zeman. He reminded the faithful that the President, though he has a symbolic role, can influence, with his actions, the moral and psychological climate of the country. “There are two personalities, two characters and two styles of action and political culture that are totally different. Your vote will also decide which of them will affect the social and political climate of our society that will represent us around the world. Let us remember the words of Vaclav Havel before the elections: may God guide your hand!” Although he did not pass any judgements during the ceremony, while he was leaving the church, stickers were handed out with the icon of Karel Schwarzenberg – but it was not enough to defeat the competitive strength of Zeman.

by Sabrina Salomoni