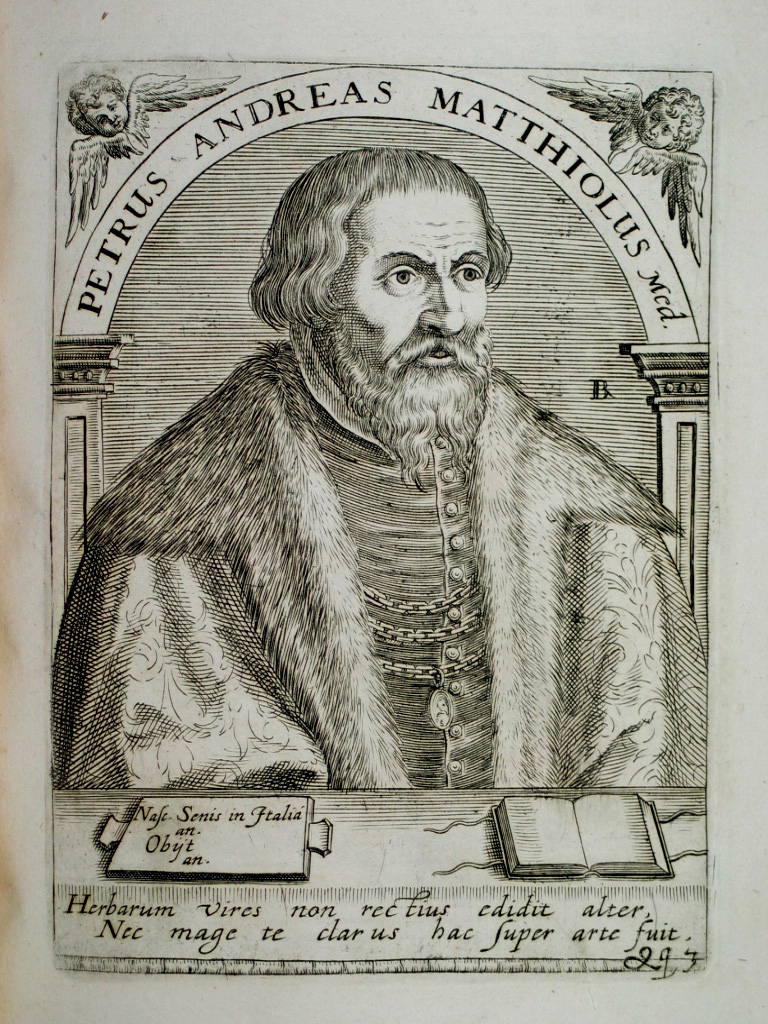

The Sienese Pietro Andrea Mattioli, the scientist who devoted his entire life to the study of plants and who published in the sixteenth century in Prague an immortal work: the Herbarium

Since ancient times, man has established an unbreakable bond with the vegetable kingdom. Besides being a valuable food source for humans, plants have been widely used in religious and magic rites in every culture and, not least, in the medical field. Among the most brilliant minds of all times, that were able to penetrate the well-kept secrets of buds, petals, stems and roots, special recognition goes to an Italian: the Sienese doctor and humanist Pietro Andrea Mattioli, who devoted all his life to the study of plants and the progress of science and who lived, not by chance, a long time in Prague, the city where he published his most important work: the famous “Herbarium”, a monumental work written in Czech, which is still widely known and appreciated today.

Among the many illustrious Italians who lived in the sixteenth and seventeenth century on Czech lands, and who contributed through their work to weave a dense network of cultural relations between Bohemia and Italy, the Sienese herbalist doctor was one of the most beloved, as reported by the historian Bohuslav Balbín (1621-1688), who stated that Mattioli was an “excellent Italian physician that due to his long stay in our Country, had became almost one of our fellow citizens”.

Among the many illustrious Italians who lived in the sixteenth and seventeenth century on Czech lands, and who contributed through their work to weave a dense network of cultural relations between Bohemia and Italy, the Sienese herbalist doctor was one of the most beloved, as reported by the historian Bohuslav Balbín (1621-1688), who stated that Mattioli was an “excellent Italian physician that due to his long stay in our Country, had became almost one of our fellow citizens”.

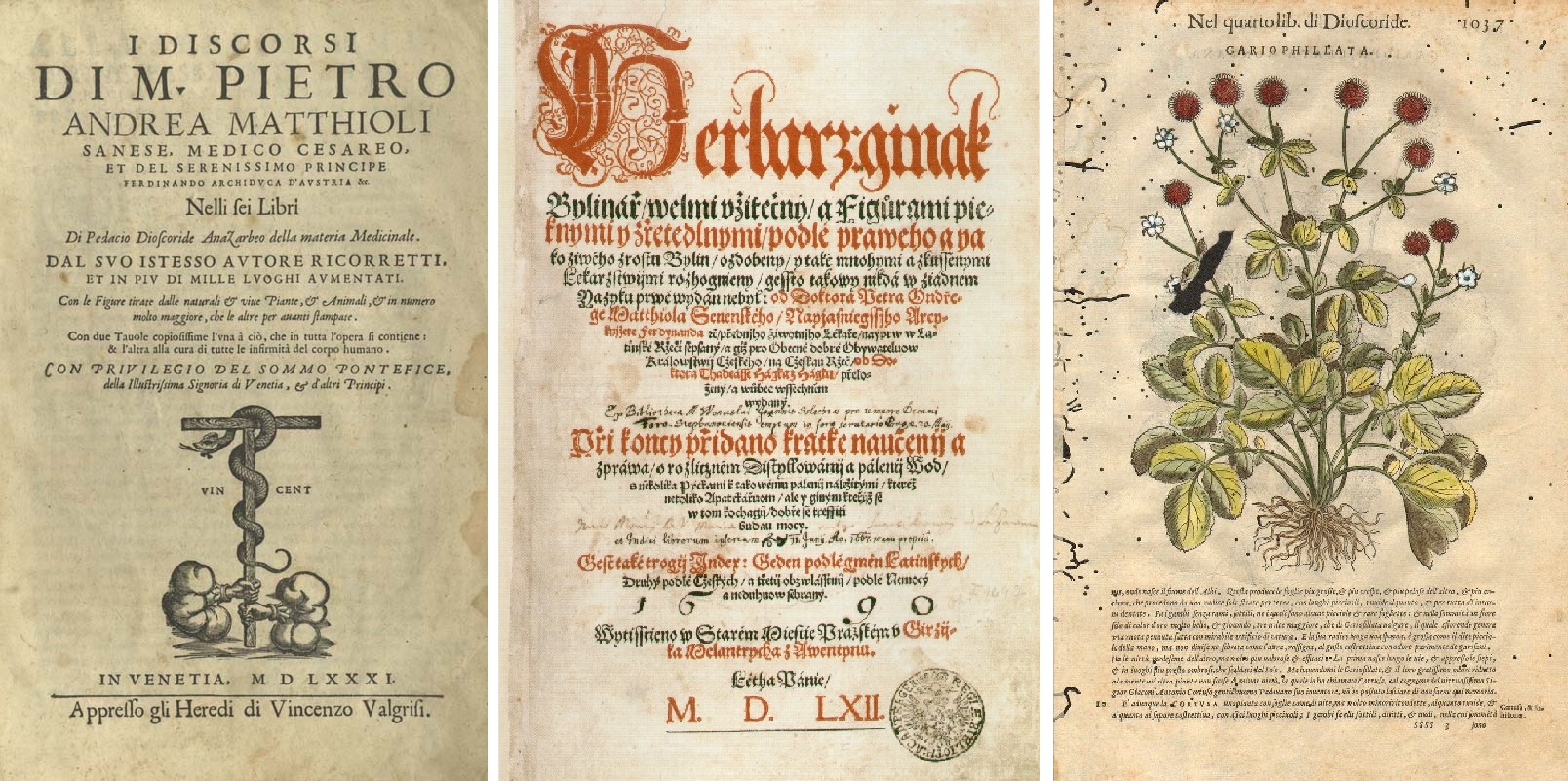

Pietro Andrea Mattioli was born in Siena in 1501, the son, along with 12 brothers, of Francesco and Lucrezia Buoninsegna. A restless spirit from a very young age and a lover of nature, Pietro Andrea studied Latin, Greek, rhetoric and philosophy in Siena and Venice and then finished his studies in medicine at Padua in 1523. He travelled extensively around Italy in order to improve his secret art: Perugia, Rome, Trento and Gorizia saw him exercising the science of Asclepius, with great successes and recognition, held in high esteem by the powerful and loved by the people, while his reputation as a great doctor also crossed the boundaries of cities and kingdoms. Mattioli spent much of his studies on treating plague, which at that time claimed numerous victims across Europe, as well as other diseases, such as syphilis. Around 1544 he was already very famous also as a botanist, thanks to his Italian translation of the work of the Greek Dioscorides on botany entitled: “On medical matters”, that Mattioli published under the title: “Di Pedacio Dioscoride Anazarbeo libri cinque Della historia & materia medicinal…”. Mattioli continued throughout his life to release new expanded versions of it and revised and improved this important volume to which he gave the name “Commentaries” alias “Herbals”, aimed at analyzing the experiences gained in the herbal field in ancient times comparing it and enriching it with modern knowledge of medicinal plants. The major turning point in the life of the wandering doctor took place in 1550, when Mattioli was asked to be the personal physician of Emperor Ferdinand I in Innsbruck. Ferdinand greatly favoured the Italian scholar and offered him the opportunity in 1555 to become the personal physician of his son Ferdinand of Tyrol. In the wake of Archduke Ferdinand, lieutenant of Czech lands, but also a lover of art and knowledge, Mattioli arrived in Prague, where he found a large community of Italian artists, architects, bricklayers and stonemasons, who built palaces and noble residences and that, shortly thereafter, were to found in 1573, on the aegis of the Society of Jesus, the “Congregation of the Blessed Virgin Mary of the Assumption”, better known as “the Italian Congregation of Prague”. The Archduke had sincere and profound respect for the Sienese therapist and when his wife gave birth to his first son, Ferdinand called him Andrea, just as his personal physician. In Bohemia Mattioli tightened his relations with humanists and scientists and married for the second time. He corresponded with doctors and herbalists from various countries, who sent to Prague known and unknown species of herbs, which he studied with great care.

Jiří Melantrich from Aventine was a Czech publisher and printer, owner of the most famous and important printing house in Prague, known not only in Bohemia but also in the whole Europe of the time. He carried out his work in a crucial period for Czech literature, which saw the birth of some of the greatest masterpieces in the national language. Melantrich obtained from the Emperor the privilege of publishing Mattioli’s “Herbals” for five years in an illustrated edition of great value, which involved the investment of a substantial capital on his part, as well as that of Mattioli and the Emperor. During the Diet in 1558, the Czech States established that from the tax money, a large sum should be paid to Mattioli for the publication of the treatise. And this great effort was amply rewarded. Mattioli accepted his work to be published in Czech in order to better serve the people of the kingdom. The preparation work lasted eight years and the volume saw the light of day only in 1562 with the title “Herbář jinak bylinář velmi užitečný”. The novelty of this edition of great worth and scientific value were its rich illustrations, painted on the bases of close, direct observations of plants, for which artists from all over the kingdom were called to work on the xilography under the direct control of Mattioli. The book is also remembered for being one of the first works in which art and science are brought closely together, thanks to the shift from a symbolic-allegorical depiction to that of a real natural element.

The “Herbarium” was a compendium of the knowledge of the period on medicinal plants and their daily use in the medical, food and cosmetic field. The book included plants that had been introduced into Europe from the Americas, such as the tomato, the sunflower and corn.

In the Czech preface, Mattioli states that he wrote it out of gratitude to the Czech people, with whom he lived for a long time: “So that they may heal and protect themselves from illness”. The Czech translation was done by the Bohemian doctor and astronomer Tadeáš Hájek from Hájek, who then became the personal physician of Emperor Rudolph II. Hájek did not simply limit himself to translating the text, but enriched it with valuable information about the native plants of Bohemia and their use. In addition, with his translation, the Bohemian physician and astronomer laid down the foundation for Czech botanic terminology.

In the Czech preface, Mattioli states that he wrote it out of gratitude to the Czech people, with whom he lived for a long time: “So that they may heal and protect themselves from illness”. The Czech translation was done by the Bohemian doctor and astronomer Tadeáš Hájek from Hájek, who then became the personal physician of Emperor Rudolph II. Hájek did not simply limit himself to translating the text, but enriched it with valuable information about the native plants of Bohemia and their use. In addition, with his translation, the Bohemian physician and astronomer laid down the foundation for Czech botanic terminology.

Following the publication of the work, Mattioli was elevated to the rank of a noble. During his years in Prague, the Sienese therapist published five volumes, but other writings by him were published in the Czech language even after his death.

Mattioli left Prague and Bohemia around 1566 and settled in Tyrol, where he married again, but continued his practice as a physician for the Imperial family. In 1578 Archduke Ferdinand sent him to Rome in order to cure his son Andreas, who in the meantime had been appointed cardinal. Mattioli obeyed, but stopping at Trento, he was infected, ironically, by the very same disease for which he had sought a remedy all of his life and which was to kill him: plague.

Even today, we owe a great deal to the brilliant Italian botanist and doctor who lived in Bohemia for more than two decades in the service of the Habsburgs. He gave, with his studies and work, an important contribution to the development of the science of medicinal herbs for therapeutic use and the dissemination of scientific knowledge throughout Europe at the time.

The “Matthiola” is a type of herbaceous perennial plant from the Mediterranean regions. These plants produce fragrant flowers ranging from yellow to red and from blue to purple, and are very popular as ornamental plants. To give it its name was the British botanist Robert Brown, who lived between the eighteenth and nineteenth century, in honour to the great Pietro Andrea Mattioli, the physician and botanist from Siena.

by Mauro Ruggiero