From Nymburk to Libeň, from Kersko to the Prague beer houses: the significant places of the most original twentieth century Czech author

To celebrate the centenary of Bohumil Hrabal, we embarked on a journey through Bohemia and Moravia, to discover the cities and towns linked to his life. The first stop in our journey was Brno Židenice. Bohumil was born in the last house in Balbínova ulice street, on 28th March, 1914. He was the son of a young woman named Marie Kiliánová and an Austrian officer, who did not recognize him as his son. Two years later, Marie married František Hrabal, the Polná brewery accountant and went to live there. But Bohumil often returned to Brno to spend his summers with his grandparents. In Polná he particularly loved to follow the band during the funeral processions, and then to the beer house where, at the age of four, he had got drunk for the first time.

In 1919 the family moved to Nymburk. Hrabal grew up in the local brewery where his father worked. Not at all keen on going to school, where he accumulated many failures, he spent much of his time near the river or playing football, but was particularly fascinated by the brewery and the various phases of production, which he reported in Cutting it short (Postřižiny). The Nymburk Brewery dedicated its Postřižinské pivo beer to him by using the title name of his book. In 1935 he then moved to Prague to study law, but was never able to forget the old Nymburk of the First Republic, the place of his happy childhood and where he built his relationship with life and literature. A place so dear to him, which in the first period he often returned to, even if only to have an evening stroll along the Elbe. “For him, Nymburk was simply the city of cities and the brewery was his castle”, wrote Tomáš Mazal, his friend and biographer. The German occupation of 1939 brought about the closure of the university, and Hrabal had to interrupt his studies. After a short period working in a notary studio and as an insurance agent, he ended up working for the railways. For two years, he directed the closely watched trains at Kostomlaty station, a job that fascinated him: “If I were to choose a jobs I did in the past, I would certainly choose to be a station master again”, he wrote in 1968, twenty-three years after leaving the railways.

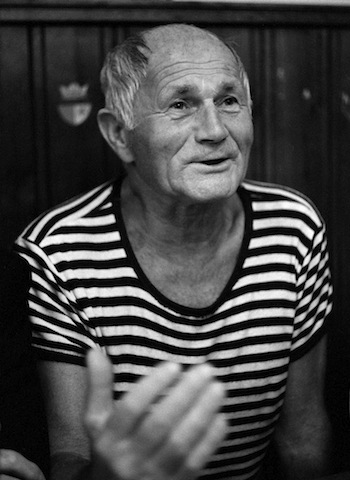

(Photo: Hana Hamplová)

He then worked a few years for the Kladno steelworks, but in 1954, after a serious accident, he ended up packaging old books that were sent to be destroyed in the Prague district of Libeň. Between 1950 and 1973 the suburb of Libeň became his home, a place of great creative inspiration and synonym of autonomy. “At the time I had the feeling that all those roads and narrow streets and beer houses and everything was meant for me and for me only, and that the suburb was waiting for me, was intended for my eyes only”. The streets, the Rokytka stream, the Bulovka hills and Hájek, “all this filled me with wonder – he wrote. – I used to go out for a walk at night and never got enough of the poetry of that suburb, with the ball shaped gasometer towering over Palmovka”. His apartment at 24 Na Hrázi (On the dike), poetically called Na Hrázi věčnosti (On the dike of eternity), has become legendary, because it is there that Hrabal used to welcome the creative Prague world of the time, including the underground philosopher and poet Egon Bondy and the figurative artist Vladimír Boudník. This street was the setting of the In-house wedding and A tender barbarian; and it was here that he met Pipsi and where they spent two decades of their happy marriage.

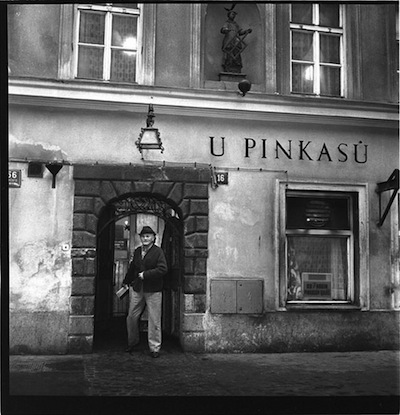

From 1959 to 1961 he worked as a stagehand and walk-on at the Divadlo pod Palmovkou theatre, then called Divadlo S.K. Neumanna. He then attended the Libeň synagogue that served as a repository for their stage objects, whilst in the freer atmosphere of the nineteen-sixties, it hosted the literary and philosophical debates of Hrabal and his friends. On completing his theatrical experience, he dedicated himself solely to the activity of writer, even if he loved working, so as to remain in contact with people, those “palaverers”, that with their lively and popular chatter proved to be an endless inspirational source for his works. He started publishing when he was already in his fifties and was immediately successful both in Czechoslovakia as well as abroad. He spent a frenetic life writing and much time at the beer house, the other place from which he drew inspiration and that allowed him to refine his writing style. Every day he frequented U Kotvy, in front of the rettery, one of the few Hrabalian places that are still open. Many of the places that hosted the writer for years, no longer exist today, whilst others have totally changed their original atmosphere, such as the U Pinkasů, where Hrabal and his wife used to sit and sip artisan beer, but which over the years has lost its fame. A place, however, that is half way between a pub and a snack bar, is Automat Svět, celebrated by the writer in the homonymous book of short stories. The Automat was part of the Palác Svět, a multi-purpose centre that housed apartments, a shopping mall and the cinema Svět. The company of the Italian Antonio Crispino, the current owner of the property, has promised for more than a decade to renovate the ruined building but, although it has been declared a cultural monument, this glimpse of the Hrabalian world seems destined to disappear.

(Photo: hrabal-nymburk.cz)

With the earnings from his first novel, Hrabal bought a small house in Kersko, a location along the Elbe in the middle of nature. In the 1970s, a period in which he could not publish, he increasingly sought refuge in these woods, and it was here that he composed his most famous literary works. He also took care of his beloved cats, so much that he used to take a daily bus from Prague to bring them something to eat.

In 1974 there was yet another transfer and this time the Hrabal family moved to Kobylisy. At the end of the 1980s their home at Libeň and half of Na Hrázi were demolished and replaced by a bus station. The site, which also has a private car park, is now called Hrabal Square. On the place where he lived, just at the exit of the Palmovka underground, the so-called Hrabal wall was erected in 1990, in his honour. This work of art by the artist Tatiana Svatošová is decorated with a portrait of Hrabal – that is over five meters high – and includes his portable typewriter Perkeo with the German keyboard with which he composed most of his works, passages from his books, the cats that kept him company, the indications pointing to the famous nearby U Hausmanů and U Horkých beer houses and the famous Automat Svět.

In the 1970s and 1980s, it is the Letná beer houses that form the setting for the “Hrabalian Wednesdays”, but the best known, for which he had a predilection, is located in the historical centre of Prague, U zlatého tygra (At the Golden Tiger). He had been a client there since the fifties but in the last decade of his life it had become a regular place for meetings with friends and other artists, as well as an office in which to work at his texts. Hrabal speaks about it in several of his works, to such an extent, that many people even come from abroad to stop here to learn about the writer, to ask for an autograph or to see the plate which bears the words “Hrabal’s table”, that is placed in the small back room. A meeting with the presidents Václav Havel and Bill Clinton was held here in 1994.

The last stage of his life and of our journey is Na Bulovce hospital. In 1997, Hrabal fell from the window of his room on the fifth floor. The fact was then dismissed as an accident while he was feeding some pigeons, but his friends, including Mazal, spoke of a suicide attempt, a chapter of life that Hrabal had repeatedly announced through his characters.

by Sabrina Salomoni