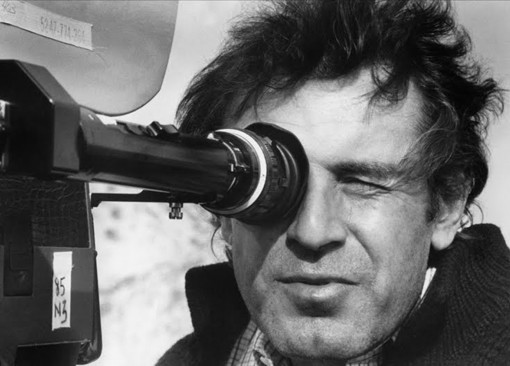

Today we celebrate the birthday of Jan Tomáš Forman, better known under his art name of Miloš Forman, the great Czech double Oscar winning film director, undoubtedly one of the most loved and discussed characters in film history

Despite a tragic childhood eclipsed by the dark shadows of Nazism, which left him scarred for his whole life, Forman is perceived as an artist celebrating life, freedom of expression, individualism and nonconformity. Many believe that the key to his success lies in his ability to maintain, in spite of his emigration to the United States, the identity and themes of his early successes in Czechoslovakia, with the same extravagant heroes, naïve but rebellious. Forman managed to adapt to the political climate of America in the seventies before dedicating himself to real life nonconformist personalities in modern day America such as Andy Kaufman and Larry Flynt. It was after the Russian occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1968, when the director made a radical decision to leave his home country for the United States, which Forman, a great admirer of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and John Ford, considered to be “the country of cinema like Egypt is the country of the Pyramids”. However, the multiple awards and his critical and commercial success have not been enough to prevent criticism from certain intellectuals and film critics who believe that Forman sold himself by exchanging a country with political censorship for one with another type of censorship – commercial. The question is: what exactly has remained from Czechoslovakian cinema in the American films of Forman?

The cinematic adventure of the master, who was born in Čáslav (central Bohemia) on the 18th of February 1932, took off in 1964 with his first full length film Černý Petr (Black Peter). The film won the Golden Sail award at the Locarno festival, while the following year his second film Lásky jedné plavovlásky (Loves of a blonde), was nominated for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar as well as the Golden Lion in Venice. From these two films you already see the signature of the artist and the direction his cinematic journey is taking. In the first film, he focuses on the problems of the young generation of his country under socialism, which deeply influenced their choices and existence. The second tells the story of Andula, a young girl in search of love and her escape from a mundane world (represented by her factory job here), but who ends up clashing with a rather different reality to the one in her dreams. The character of Andula is the first real hero (heroine) in Forman’s cinema and displays the free spirit but also the naïvety of the protagonists of his American works such as Randle McMurphy, memorably played by Jack Nicholson in his masterpiece One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s nest. However, it was the following film which identified him as one of Europe’s most important directors, as well as one of the more controversial. Hoří, má panenko (The Fireman’s ball), from 1967, the last Czechoslovakian film, is set in a Bohemian village where the firemen organize a ball in which nothing goes according to plan: someone steals the raffle prize, the beauty contest is a failure, and a fire eventually ends the evening. Forman has often claimed that the film, an Italian co-production is nothing more than a satire of provincial customs and that there is no hidden symbolism or deeper political meaning, but the censors and parficularly Antonín Novotný, the president at the time, understood that the crafty director aimed at higher targets and the film was consequently banned. There was indeed so much controversy generated by the film that even the Italian producer, the legendary Carlo Ponti, abandoned the project forcing the Bohemian cineaste to turn to French producers.

The censorship applied in reaction to the release of Forman’s masterpiece indicate why the choice to change country was not really so unpredictable. Nevertheless, there is certainly not a scarce number of people who believe that these early Czechoslovakian works of the director, are actually richer in substance and stand out due to their complexity, especially since the censorship forced directors to make more cryptic, multilayered films. Slavoj Žižek, the popular philosopher and cultural critic is a member of this camp. Žižek, has made it clear numerous times that while he does feel nostalgia towards communism, the conditions at the time resulted in the creation of more authentic works of art. He underlines that in his opinion, both Forman and the Polish director Krzysztof Kieślowski made more interesting films in their home countries than in their adopted countries (France in Kieślowski’s case). That said, Žižek has also declared his love for the first American film of the Czech director, Taking Off, the winner of the Grand Prix at the 24th Cannes film festival in 1971. Despite being a box-office flop Taking Off remains the most underrated film of Forman, though it is slowly getting the critical recognition it deserves. The film is a biting satire on generation clashes, focussing on the difficult relationships between parents and children, in a return to the themes of his first films such as Lásky jedné plavovlásky. This time, the protagonists are the parents, who in the search for their runaway children, learn to smoke Marijuana and play strip poker in order to understand their generation more. As the Slovenian intellectual explains, it is fascinating because “Forman tries to interpret the American middle class through Czech glasses”. It is perhaps the fact that America is depicted from a foreigner’s perspective that the public were unable to fully understand the film when it was released.

The following Forman films, at first glance seem more “American”, in that they are set in America and are often based on novels or real life personas from the country. So it seems, but in reality the director never abandoned the topics of his early works. His first commercial success arrived in 1975 with One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, one of the few films in film history to have won all the main Oscars (best film, best director, best actor, best actress, best non-original screenplay) and was both a critical and a commerical success. The film is only more “western” on the surface since it was adapted from the novel by the American writer Ken Kasey and the action takes place within the walls of the Oregon State Hospital. However, the powerful metaphor of the novel, of rebellion against an oppressive society who want to make those who don’t accept the conditions imposed on them dumber or in the worst cases lobotomize them, really is a perfect match for an emigrant from a communist country, providing material he could get his teeth into. It is no coincidence that Forman chose it. Even if the famous final break-out scene in which the indian runs to freedom after pulling the marble basin out of the ground and hurling it threw the window, was considered a scene about America, Forman sees it differently. In an interview with the BBC shortly after the release of his film Man on the Moon, Forman stated that the scene for him represented “the dream of 99% of the younger generation in communist countries”, because they could not travel and therefore felt like they were in a zoo, with desire to climb over the fences and see the world. The talent of Forman also lies in his ability to create a cinema which simultaneously comments on oppression in both communist and capitalist societies.

The themes of freedom and individualism are prevalent in the entire filmography of the master. Even his most acclaimed, awarded film (8 Oscars) Amadeus (1984), which marked the first return to his homeland since his voluntary self-exile, explores the troubled relationship between an artist (Mozart) and the authorities, granting Forman the possibility to attack his countrys’ censors again. He often reiterates that if he had to choose between the political censorship of his country and the commercial pressures of Hollywood he will always prefer the second since in this case the spectators determine the artistic choices, and not “an idiot”, with a specific ideology to quote Forman himself. The film gave him the opportunity to express his thoughts on censorship in general. However, from this perspective a key work in his oeuvre is The People vs. Larry Flynt, (1996), a biography of the eccentric, nonconformist businessman who founded the magazine Hustler. Featuring a protagonist that one could certainly define as “Formanesque”, the director uses the experience from his early Czechoslovakian period to explore the delicate issue of freedom of expression, with his usual doses of smart, satirical bite. Forman, chose another mould-breaking eccentric personality for his following film Man on the Moon (1999) with an outstanding Jim Carrey in the role of controversial American comedian Andy Kaufman. In this case Forman once again demonstrates his passion for individuals refusing to conform to the norm. The film would go on to win the Silver Bear for best direction at the Berlin Film Festival.

Ultimately, it is true that Forman, in certain films has decided to explore American society specifically with Hair being a good example, in which the director expresses his opinion on the Vietnam war and the beat generation creating an iconic antimilitarist work. The cineaste however, has always managed to leave his signature on his projects, and his origins are evident in all of his films, whilst also choosing themes extremely carefully. The topics of individualism, freedom, generation gap issues are as synonymous with the name of Miloš Forman as the name of his director of photography Miroslav Ondříček, who worked with the director from his early Czechoslovakian films. It was the faithful collaborator of the Bohemian, who some years ago revealed the reason for which Forman has now abandoned his trade to the magazine Blesk: a serious pathology which affecting his eyes. The artist however, has not completely left the film world behind and still has fun acting, reminding us of his motto “a director is a bit of everything: a bit of an actor, a bit of an editor, a bit of a costume designer. A good director is one who can choose much better professionals than himself for these roles”. That said, his absence as a director will leave a void in world cinema, one which will be extremely difficult to fill for the younger generations of European and American cinema.

by Lawrence Formisano